de galeno ao homem da cobra

“Chamanes et psychanalystes”

CLAUDE LÉVI-STRAUSS (1949)

Source: J. Narby et Fr. Huxley, Chamanes au fil du temps, Albin Michel, 2002

L’anthropologue français Claude Lévi-Strauss fit remarquer l’interface entre le chamanisme et la psychanalyse dans un petit article intitulé í« L’efficacité symbolique í». Son analyse se réfí¨re í la description d’une séance de guérison chamanique chez les Indiens Cuna du Panama. Lévi-Strauss cristallise la différence entre le praticien symboliste et le psychanalyste : ce dernier écoute, tandis que le chamane parle.

La cure consisterait donc í rendre pensable une situation donnée d’abord en termes affectifs et acceptables pour l’esprit des douleurs que le corps se refuse í tolérer. Que la mythologie du chaman ne corresponde pas í une réalité objective n’a pas d’importance : la malade y croit, et elle est membre d’une société qui y croit. Les esprits protecteurs et les esprits malfaisants, les monstres surnaturels et les animaux magiques font partie d’un systí¨me cohérent qui fonde la conception indigí¨ne de l’univers. La malade les accepte, ou, plus exactement, elle ne les a jamais mis en doute. Ce qu’elle n’accepte pas, ce sont des douleurs incohérentes et arbitraires, qui, elles, constituent un élément étranger í son systí¨me, mais que, par l’appel au mythe, le chaman va replacer dans un ensemble oí¹ tout se tient.

Mais la malade, ayant compris, ne fait pas que se résigner: elle guérit. Et rien de tel ne se produit chez nos malades, quand on leur a expliqué la cause de leurs désordres en invoquant des sécrétions, des microbes ou des virus. On nous accusera peut-être de paradoxe si nous répondons que la raison en est que les microbes existent, et que les monstres n’existent pas. Et cependant, la relation entre microbe et maladie est extérieure í l’esprit du patient, c’est une relation de cause í effet ; tandis que la relation entre monstre et maladie est intérieure í ce même esprit, conscient ou inconscient : c’est une relation de symbole í chose symbolisée, ou, pour employer le vocabulaire des linguistes, de signifiant í signifié. Le chaman fournit í sa malade un langage, dans lequel peuvent s’exprimer immédiatement des états informulés, et autrement informulables. Et c’est le passage í cette expression verbale (qui permet, en même temps, de vivre sous une forme ordonnée et intelligible une expérience actuelle, mais, sans cela, anarchique et ineffable) qui provoque le déblocage du processus physiologique, c’est-í -dire la réorganisation, dans un sens favorable, de la séquence dont la malade subit le déroulement.

A cet égard, la cure chamanique se place í moitié entre notre médecine organique et des thérapeutiques psychologiques comme la psychanalyse. Son originalité provient de ce qu’elle applique í un trouble organique une méthode trí¨s voisine de ces dernií¨res. Comment cela est-il possible ? Une comparaison plus serrée entre chamanisme et psychanalyse (et qui ne comporte, dans notre pensée, aucune intention désobligeante pour celle-ci) permettra de préciser ce point.

Dans les deux cas, on se propose d’amener í la conscience des conflits et des résistances restés jusqu’alors inconscients, soit en raison de leur refoulement par d’autres forces psychologiques, soit – dans le cas de l’accouchement – í cause de leur nature propre, qui n’est pas psychique, mais organique, ou même simplement mécanique. Dans les deux cas aussi, les conflits et les résistances se dissolvent, non du fait de la connaissance, réelle ou supposée, que la malade en acquiert progressivement, mais parce que cette connaissance rend possible une expérience spécifique, au cours de laquelle les conflits se réalisent dans un ordre et sur un plan qui permettent leur libre déroulement et conduisent í leur dénouement. Cette expérience vécue reçoit, en psychanalyse, le nom d’abréaction. On sait qu’elle a pour condition l’intervention non provoquée de l’analyste, qui surgit dans les conflits du malade, par le double mécanisme du transfert, comme un protagoniste de chair et de sang, et vis-í -vis duquel ce dernier peut rétablir et expliciter une situation initiale restée informulée.

Tous ces caractí¨res se retrouvent dans la cure chamanique. Lí aussi, il s’agit de susciter une expérience, et, dans la mesure oí¹ cette expérience s’organise, des mécanismes placés en dehors du contrôle du sujet se rí¨glent spontanément pour aboutir í un fonctionnement ordonné. Le chaman a le même double rôle que le psychanalyste : un premier rôle – d’auditeur pour le psychanalyste, et d’orateur pour le chaman – établit une relation immédiate avec la conscience (et médiate avec l’inconscient) du malade. C’est le rôle de l’incantation proprement dite. Mais le chaman ne fait pas que proférer l’incantation : il en est le héros, puisque c’est lui qui péní¨tre dans les organes menacés í la tête du bataillon surnaturel des esprits, et qui libí¨re l’âme captive. Dans ce sens, il s’incarne, comme le psychanalyste objet du transfert, pour devenir, grâce aux représentations induites dans l’esprit du malade, le protagoniste réel du conflit que celui-ci expérimente í mi-chemin entre le monde organique et le monde psychique. Le malade atteint de névrose liquide un mythe individuel en s’opposant í un psychanalyste réel; l’accouchée indigí¨ne surmonte un désordre organique véritable en s’identifiant í un chaman mythiquement transposé.

Le parallélisme n’exclut donc pas des différences. On ne s’en étonnera pas, si l’on prête attention au caractí¨re, psychique dans un cas, et organique dans l’autre, du trouble qu’il s’agit de guérir. En fait, la cure chamanique semble être un exact équivalent de la cure psychanalytique, mais avec une inversion de tous les termes. Toutes deux visent í provoquer une expérience ; et toutes deux y parviennent en reconstituant un mythe que le malade doit vivre, ou revivre. Mais, dans un cas, c’est un mythe individuel que le malade construit í l’aide d’éléments tirés de son passé ; dans l’autre, c’est un mythe social, que le malade reçoit de l’extérieur, et qui ne correspond pas í un état personnel ancien. Pour préparer l’abréaction qui devient alors une í« adréaction í», le psychanalyste écoute, tandis que le chaman parle.

Sala Kernel (17th century version)

Vista interna da nave principal da Igreja da redução guarani-jesuíta de São Miguel Arcanjo. (Patrimônio Mundial da Humanidade em 1983 pela UNESCO).

Photo: Mathieu Struck

http://conserto.organismo.art.br

Início da montagem da Sala kernel

Re-alocação física do espaço

Habilitação dos pontos lógicos de rede e disponibilização de IPs válidos para Montagem de servidor (pelos técnicos da celepar)

Instalação de ponto de acesso sem fio (wireless)

Deslocamento de seis computadores do laboratório para a sala kernel

Atualização da versão das distribuições linux (debian sarge para etch) instaladas nas estações citadas

Configuração das estações para propositos específicos de áudio, gráfico, vídeo e streaming

Estação para streaming (metronomo e pulso maestro + impressora matricial)

Criação do website conserto.organismo.art.br

Criação de identidade visual, montagem do “template” e produção de conteúdo)

Documentação em foto e vídeo de etapas do processo

Inicio da montagem de laboratório de í udio (equipamento da orquestra organismo). microfones, mesa de som, teclado midi, instrumentos musicais

Ações em andamento

– Recitação da obra de Erico Veríssimo “O tempo e o Vento” por Salvio Nienkí¶tter ( recitação da obra completa durante a mostra )

– Rodada de discuções sobre o Forum Social do Mercosul (via rede com Newton Goto)

– Recepção e entrevista com os artistas croatas Kruno Jost e Tanja Topolovec – Kruno Jost desenvolve pesquisa sobre os circuitos de arte e tecnologia no Brasil. Link para a sua página na web (http://www.uke.hr/brazil/)

– Experimentações e primeiras derivações da série dodecafônica “contrato” em seus desdobramentos retrógrado, invertido e retrógrado invertido

Motetos

“Entardecia e padre Alonzo terminava a sua aula de música. Um dos estudantes tocara ao órgão, havia pouco, uma sonatina. Depois o quarteto executara uma sarabanda, e agora o índio Rafael ali estava a tocar em sua clarineta a pavana de um compositor italiano. Havia na redução excelentes organistas, harpistas, corneteiros e clarinetistas. Tocavam composições difíceis e até trechos de í²pera italiana. Os instrumentos, em sua maioria, eram fabricados na redução pelos próprios índios, dirigidos pelos padres ”

Érico Verissimo – O tempo e o vento (I vol – O continente)

descrição de um epsódio ocorrido numa das 7 missões em 1747

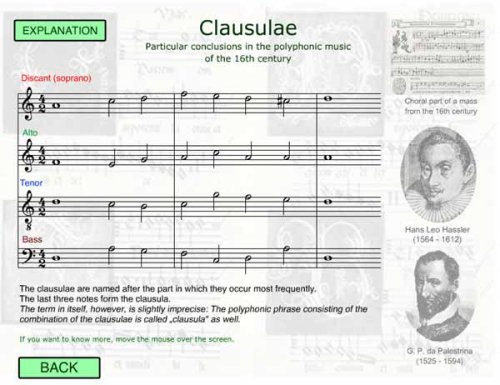

Perotin and other composers created “clausulae” — polyphonic sections of discant organum that could be inserted as replacement or substitute sections of organum into a larger work. The tenor of clausulae consisted typically of a single word from the chant, so clausulae were not independent pieces. Tenor parts often used the rhythmic modes and included repetitions.

When, in the late 12th century, some unknown composers began adding new text to the duplum of a clausula, an independent piece was created apart from the liturgy. The texted line was called the “motetus.” (The French “mot” = word, indicating the presence of text different from the cantus firmus.) The pieces themselves, called “motets,” became the predominant source of interest for composers and vehicles for experimentation during the late Middle Ages. The motet drove sacred music towards secularization when occasionally a secular cantus firmus replaced the liturgical tenor as the spine of a piece. Initially the motetus was Latin, but increasingly the added lines (motetus, triplum, etc.) were secular, most often French. This music was retrospectively named “Ars Antiqua” by theorists of “Ars Nova” which followed.

The cantus firmus was still sacrosanct but without rhythmic obligation, so one could tinker with it rhythmically. “Isorhythmic” works appeared, in which a rhythmic pattern drives the piece and encounters various melodic embodiments.

French secular texts were often substituted for Latin sacred words in motets, and sometimes two and three poems were sung simultaneously. This seems to be the most complex musical form ever to appear on the face of the earth. Motet names consist of the first words of each voice in order from top to bottom voices. Thus, motets have names such as “Plus bele que flor / Quant revient / L’autrier joer / Flos Filius” — since there are four very independent texts, in different languages, for four different musical voices and lines. This particular piece superimposes a description of the shining beauty of Mary onto the evocation of an amorous encounter onto the action of God in summer, the season of love. “A Paris / On parole / Frese nouvele” offers a street-vendor’s call in the tenor (“Fresh strawberries! Nice blackberries!”) and celebrations of the wonders of Parisian life simultaneously.

Johannes de Grocheo, a theorist writing around 1300, observed that a motet “ought not to be performed in the presence of common people, for they would not perceive its subtlety, nor take pleasure in its sound.” Instead, motets should be performed only “in the presence of learned persons and those who seek after subtleties in art.” (Bonds 61)

Also lumped in with late 12th- and 13th-century Ars Antiqua is the “conductus,” a form that became more popular when it became polyphonic. A conductus is similar to a hymn but more rhythmic (triple divisions typically), typically a metrical Latin poem, not a chant melody, rendered in two to four voices and serving as a processional piece (think “Pomp and Circumstance” or the famous wedding marches for now instrumental versions serving a similar kind of function). Though syllabic, a conductus might end with a melisma, called a “cauda” (similar later to “coda”).

Also interesting as a special effect was a technique that, when used extensively, came to lend its name to the musical piece itself: the “hocket.” This is a hiccup effect used as a compositional device that breaks up the melodic line and creates a kind of quick ping-pong acoustical trick.

páginas de origem:

www.wsu.edu/~delahoyd/medieval/motets.html – 5k

musicweb.koncon.nl/overview/clausul – 8k

Pontes de Safena

Juramento de Hipócrates

” Eu juro, por Apolo médico, por Esculápio, Hígia e Panacea, e tomo por testemunhas todos os deuses e todas as deusas, cumprir segundo meu poder e minha razão, a promessa que se segue: estimar, tanto quanto a meus pais, aquele que me ensinou esta arte; fazer vida comum e, se necessário for, com ele partilhar meus bens; ter seus filhos por meus próprios irmãos; ensinar-lhes esta arte, se eles tiverem necessidade de aprendê-la, sem remuneração e nem compromisso escrito; fazer participar dos preceitos, das lições e de todo o resto do ensino, meus filhos, os de meu mestre e os discípulos inscritos segundo os regulamentos da profissão, porém, só a estes.

Aplicarei os regimes para o bem do doente segundo o meu poder e entendimento, nunca para causar dano ou mal a alguém.

A ninguém darei por comprazer, nem remédio mortal nem um conselho que induza a perda. Do mesmo modo não darei a nenhuma mulher uma substância abortiva.

Conservarei imaculada minha vida e minha arte. Não praticarei a talha, mesmo sobre um calculoso confirmado; deixarei essa operação aos práticos que disso cuidam.

Em toda a casa, aí entrarei para o bem dos doentes, mantendo-me longe de todo o dano voluntário e de toda a sedução sobretudo longe dos prazeres do amor, com as mulheres ou com os homens livres ou escravizados.

àquilo que no exercício ou fora do exercício da profissão e no convívio da sociedade, eu tiver visto ou ouvido, que não seja preciso divulgar, eu conservarei inteiramente secreto.

Se eu cumprir este juramento com fidelidade, que me seja dado gozar felizmente da vida e da minha profissão, honrado para sempre entre os homens; se eu dele me afastar ou infringir, o contrário aconteça.”

— DIALÉTICA —- ser ou não ser eis a questão:

—->

O PLS no 25/2002 – A LEI DO ATO MÉDICO

O PLS no 25/2002 objetiva tão-somente regulamentar os atos médicos, fortalecendo o conceito de equipe de saúde e respeitando as esferas de competência de cada profissional. Em nenhuma linha encontraremos violações de direitos adquiridos, arrogância ou prepotência em relação aos demais membros da equipe. Ninguém trabalha pela saúde da população sozinho, e muito menos sem a presença do médico. A análise do conteúdo dos cinco artigos do Projeto mostra a relevância da matéria, permitindo maior compreensão acerca da importância de sua aprovação.

Artigo 1ú – A definição

Art. 1ú – Ato médico é todo procedimento técnico-profissional praticado por médico habilitado e dirigido para:

1. A prevenção primária, definida como a promoção da saúde e a prevenção da ocorrência de enfermidades ou profilaxia;

2. A prevenção secundária, definida como a prevenção da evolução das enfermidades ou execução de procedimentos diagnósticos ou terapêuticos;

3. A prevenção terciária, definida como a prevenção da invalidez ou reabilitação dos enfermos.

O Projeto tem como objetivo definir, em lei, o alcance e o limite do ato médico. Para tanto, este artigo 1ú expõe de maneira clara a definição adotada pela Organização Mundial da Saúde no tocante í s ações médicas que visam ao benefício do indivíduo e da coletividade, estabelecendo a prevenção, em seus diversos estágios, como parâmetro para a cura e o alívio do sofrimento humano.

A definição do ato médico foi elaborada com base nesta ordenação de idéias porque, na medida em que abrange todas as possibilidades de referir procedimentos profissionais na área da saúde, essa classificação pareceu ao autor a melhor maneira de sintetizar clara e lealmente os limites da atividade dos médicos. Com sua utilização, parece ser possível diferenciar o que se deve considerar como atividade privativa dos médicos e quais os procedimentos sanitários que não o são.

Como se vê, o conceito de cura não se opõe ao de prevenção, vez que a cura, quer com o sentido de tratamento quer como resultado dele, está implícita na prevenção secundária. Razão pela qual não faz sentido opor a medicina curativa í medicina preventiva, posto que aquela é parte integrante desta.

O inciso I trata da atenção primária, que cuida de prevenir a ocorrência de doenças, através de métodos profiláticos, e das ações que visem í promoção da saúde para toda a população. A prevenção primária reúne um conjunto de ações que não são privativas dos médicos; ao contrário, para que obtenham êxito exigem a co-participação de outros profissionais de saúde e até mesmo da população envolvida.

O inciso II, por sua vez, estabelece os atos que são privativos dos médicos. São aqueles que envolvem o diagnóstico de doenças e as indicações terapêuticas, atributos que têm no médico o único profissional habilitado e preparado para exercê-los, além dos odontólogos em sua área de atuação.

Não se incluem, aqui, os diagnósticos fisiológicos (funcionais) e os psicológicos, que são compartilhados com outros profissionais da área de saúde, como os fisioterapeutas e os psicólogos. O diagnóstico fisiológico se refere ao reconhecimento de um estado do desenvolvimento somático ou da funcionalidade de algum órgão ou sistema corporal. O diagnóstico psicológico se refere ao reconhecimento de um estado do desenvolvimento psíquico ou da situação de ajustamento de uma pessoa. No entanto, quanto se trata do diagnóstico de enfermidades e da indicação de condutas para o tratamento, somente o médico e o odontólogo, este em sua área específica, possuem a habilitação exigida para tais ações. E os médicos veterinários, no que diz respeito aos animais.

O inciso III aborda as atividades de recuperação e reabilitação, também compartilhadas entre a equipe de saúde. Não são atos privativos dos médicos. Por medidas ou procedimentos de reabilitação devem ser entendidos os atos profissionais destinados a devolver a integridade estrutural ou funcional perdida ou prejudicada por uma enfermidade (com o sentido de qualquer condição patológica).

Os dois parágrafos que complementam este artigo explicitam quais os atos privativos dos médicos e os compartilhados com outros profissionais:

ç 1ú – As atividades de prevenção de que trata este artigo, que envolvam procedimentos diagnósticos de enfermidades ou impliquem em indicação terapêutica, são atos privativos do profissional médico.

ç 2ú – As atividades de prevenção primária e terciária que não impliquem na execução de diagnósticos e indicações terapêuticas podem ser atos profissionais compartilhados com outros profissionais da área da saúde, dentro dos limites impostos pela legislação pertinente.

Há um consenso indubitável acerca destes conceitos, estabelecidos há milênios pela prática da Medicina. Diante da estupefação de alguns pela inexistência, até hoje, de lei que afirmasse o óbvio, vale esclarecer que nunca houve tal necessidade antes, o que só agora se impõe em virtude do crescimento de outras profissões na área da saúde. Estabelecer limites e definir a abrangência do ato médico passou a constituir um assunto de extremo interesse de toda a sociedade, e não apenas dos médicos.

Artigo 2ú – Atribuições do CFM

Art. 2ú – Compete ao Conselho Federal de Medicina, nos termos do artigo anterior e respeitada a legislação pertinente, definir, por meio de resolução, os procedimentos médicos experimentais, os aceitos e os vedados, para utilização pelos profissionais médicos.

Este artigo estabelece a competência do Conselho Federal de Medicina em definir os atos médicos vedados, os aceitos e os experimentais, í luz da ética e do conhecimento científico existente.

Vale ressaltar que o estabelecimento de atribuições em lei para os conselhos federais de fiscalização profissional não constitui inovação para o dos médicos. A análise das leis que regulamentam outras profissões da área de saúde assim o demonstra:

DECRETO no. 88.439/83 – Biomedicina

Art. 12ú – Compete ao Conselho Federal:

XVIII – Definir o limite de competência no exercício profissional, conforme os currículos efetivamente realizados.

LEI no 3.820/60 – Farmácia

Art. 6ú – São atribuições do Conselho Federal:

g) expedir as resoluções que se tornarem necessárias para a fiel interpretação e execução da presente lei;

j) deliberar sobre questões oriundas do exercício de atividades afins í s do farmacêutico;

l) ampliar o limite de competência do exercício profissional, conforme o currículo escolar ou mediante curso ou prova de especialização realizado ou prestada em escola ou instituto oficial;

m) expedir resoluções, definindo ou modificando atribuições ou competência dos profissionais de Farmácia, conforme as necessidades futuras;

Parágrafo único – As questões referentes í s atividades afins com as outras profissões serão resolvidas através de entendimentos com as entidades reguladoras dessas profissões.

LEI no. 5.766/71 – Psicologia

Art. 6ú – São atribuições do Conselho Federal:

d) definir, nos termos legais, o limite de competência do exercício profissional, conforme os cursos realizados ou provas de especialização prestadas em escolas ou institutos profissionais reconhecidos;

n) propor ao Poder Competente alterações da legislação relativa ao exercício da profissão de Psicólogo;

Artigo 3ú – As atividades de direção e chefia médicas

Art. 3ú – As atividades de coordenação, direção, chefia, perícia, auditoria, supervisão, desde que vinculadas, de forma imediata e direta a procedimentos médicos e, ainda, as atividades de ensino dos procedimentos médicos privativos, incluem-se entre os atos médicos e devem ser unicamente exercidos por médicos.

Este artigo preconiza que os cargos de direção e chefia diretamente relacionados aos atos médicos sejam exercidos exclusivamente por médicos. Não há nada de extraordinário nisso. As leis que regulamentam as outras profissões da saúde sempre realçaram este quesito, garantindo-lhes as chefias de enfermagem, nutrição etc. Senão, vejamos:

LEI no. 8.234/91 – Nutrição

Art. 3í° – São atividades privativas dos nutricionistas:

I – direção, coordenação e supervisão de cursos de graduação em nutrição;

V – ensino das disciplinas de nutrição e alimentação nos cursos de graduação da área de saúde e outras afins;

VI – auditorias, consultorias e assessoria em nutrição e dietéticas;

DECRETO no 85.878/81 – Farmácia

Art 1ú – São atribuições privativas dos profissionais farmacêuticos:

II – assessoramento e responsabilidade técnica em:

a) estabelecimentos industriais farmacêuticos em que se fabriquem produtos que tenham indicações e/ou ações terapêuticas, anestésicos ou auxiliares de diagnóstico, ou capazes de criar dependência física ou psíquica;

b) órgãos, laboratórios, setores ou estabelecimentos farmacêuticos em que se executem controle e/ou inspeção de qualidade, análise prévia, análise de controle e análise fiscal de produtos que tenham destinação terapêutica, anestésica ou auxiliar de diagnósticos ou capazes de determinar dependência física ou psíquica;

IV – a elaboração de laudos técnicos e a realização de perícias técnico-legais relacionadas com atividades, produtos, fórmulas, processos e métodos farmacêuticos ou de natureza farmacêutica;

V – o magistério superior das matérias privativas constantes do currículo próprio do curso de formação farmacêutica, obedecida a legislação do ensino;

DECRETO no 53.464/64 – Psicologia

Art. 4ú – São funções do Psicólogo:

II – Dirigir serviços de Psicologia em órgãos e estabelecimentos públicos, autárquicos, paraestatais, de economia mista e particulares.

III – Ensinar as cadeiras ou disciplinas de Psicologia nos vários níveis de ensino, observadas as demais exigências da legislação em vigor.

VI – Realizar perícias e emitir pareceres sobre a matéria de Psicologia.

LEI no 6.965/81 – Fonoaudiologia

Art. 4ú – É da competência do Fonoaudiólogo e de profissionais habilitados na forma da legislação específica:

g) Lecionar teoria e prática fonoaudiológicas;

h) Dirigir serviços de Fonoaudiologia em estabelecimentos públicos, privados, autárquicos e mistos;

LEI N. 7.498/86 – Enfermagem

Art. 11 – O Enfermeiro exerce todas as atividades de Enfermagem cabendo-lhe:

I – privativamente:

a) Direção do órgão de enfermagem integrante da estrutura básica da instituição de saúde, pública e privada, e chefia de serviço e de unidade de enfermagem;

c) Planejamento, organização, coordenação, execução e avaliação dos serviços de assistência de enfermagem;

h) Consultoria, auditoria e emissão de parecer sobre matéria de enfermagem;

Com o intuito de aclarar essa intenção, o parágrafo único deste artigo dissipa todas as dúvidas que poderiam existir:

Parágrafo único – Excetuam-se da exclusividade médica prevista no caput deste artigo as funções de direção administrativa dos estabelecimentos de saúde e as demais atividades de direção, chefia, perícia, auditoria ou supervisão que dispensem formação médica como elemento essencial í realização de seus objetivos ou exijam qualificação profissional de outra natureza.

Uma direção administrativa, uma secretaria ou até mesmo o Ministério da Saúde podem ser cargos exercidos por profissionais não-médicos desde que, em respeito í lei, haja um responsável técnico médico para responder pelas questões técnicas e éticas que envolvam aquela instância administrativa. Nenhuma novidade neste passado recente de nosso país. Os dois últimos titulares da Pasta da Saúde, por exemplo, foram economistas.

Artigo 4ú – O exercício ilegal da Medicina

Art. 4ú – A infração aos dispositivos desta lei configura crime de exercício ilegal da Medicina, nos termos do Código Penal Brasileiro.

O exercício ilegal da Medicina é crime, tipificado no Código Penal Brasileiro em seu artigo 283. Ressalte-se que este artigo reforça o preceito legal, lembrando que a profissão médica requer habilitação, aqui entendida como a legalização de uma atividade social regulamentada.

Artigo 5ú – O respeito í s outras profissões regulamentadas

Art. 5ú – O disposto nesta lei não se aplica ao exercício da Odontologia e da Medicina Veterinária, nem a outras profissões de saúde regulamentadas por lei, ressalvados os limites de atuação de cada uma delas.

Se alguma dúvida havia acerca da extrapolação de direitos, este artigo a desfaz completamente. O objetivo deste Projeto restringe-se simplesmente a definir a abrangência e os limites dos atos médicos, resguardando as prerrogativas definidas em lei para as outras profissões da área de saúde.

sobre a arte de construir pontes

. Spring Story – The Vernal Aeration ., by 3amfromkyoto

Lesson II: Forces at Work

In our study of bridges, we use the example of the suspension bridge to identify load, where load comes from, and distinguish between “dead” and “live” loads. Groups of students form a “human suspension bridge” to feel how loads are distributed in the bridge, and to identify the parts of the bridge that experience tension or compression in response to the applied loads.

. Of Food, Appetites And The Human Condition ., by 3amfromkyoto.

Lesson III: Stress Test

Stress isn�t just that feeling you get when you have a million things to do and only five minutes in which to do them! Engineers calculate stresses in buildings and bridges in order to ensure that the materials aren�t experiencing more stress than they can take, which could result in collapse. In this lesson, students learn what stress means to engineers and, through experimentation, determine failure stresses for a variety of household materials, as the next step in the quest to build a structurally sound model bridge.

Source: The art of bridge construction.

A arte está morta, vou buscar a pá.

Uma coisa é a coisa

Outra é a palavra coisa

voz1: O que a gente faz não é bom, não é ruim, não é NADA.

a gente não vai ser lembrado por isso(…)

(…)a gente não faz nada do que a gente ja não faz várias vezes(…)voz2: será que não seria mais útil a gente gravar aquele barulho(…)

voz1: isso pode ser tão redundante quanto essa nossa conversa.

o que está na cara?

– OLHOS DA CARA

Eye of the Beholder

0ê semana – ADíGIO

Para quem é oferecido o ConSerto?

ConSerto busca em suas experimentações o diálogo direto com duas categorias de público:

Um mais ativo, o qual de imediato se interessa pelas ações e se propõe a participar presencialmente das jams, performances, curtas e produções em geral. Formadores de opinião, possuem consciência e intenção de ações poéticas. São protagonistas e criadores de um cenário cultural e convergem, de algum modo, com as propostas elaboradas pela Orquestra Organismo. Músicos, atores, artistas, poetas, hackers encontram maneiras de trabalhar com complementariedade de linguagens em um espaço ocupado para criar novos significados seguindo a idéia de código aberto.

Um segundo público interessado prefere agir como observador/contemplador. A ele é dada a oportunidade de protagonizar ações possibilitando a compreensão do processo aberto como algo tão ou mais poético que os “produtos culturais” gerados. Por meio de palestras convocadas sob demanda, estas pessoas podem discutir desde as técnicas das ferramentas até os conceitos envolvidos, assim participando e compreendendo a profundidade do trabalho que está sendo realizado. Busca que este público sinta-se cada vez mais seguro de seu papel como agente cultural, í vontade para interagir.

(Continue a ler em ConSerto).

retinoscopia 0)-(0 moscasvolantes

preparativos da ação

preparativos da ação

Fault tolerance

El Golem

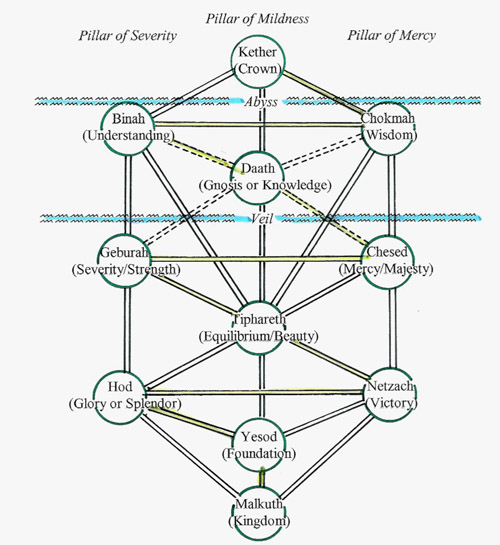

Si (como afirma el griego en el Cratilo)

el nombre es arquetipo de la cosa

en las letras de ‘rosa’ está la rosa

y todo el Nilo en la palabra ‘Nilo’.

Y, hecho de consonantes y vocales,

habrá un terrible Nombre, que la esencia

cifre de Dios y que la Omnipotencia

guarde en letras y sílabas cabales.

Adán y las estrellas lo supieron

en el Jardín. La herrumbre del pecado

(dicen los cabalistas) lo ha borrado

y las generaciones lo perdieron.

Los artificios y el candor del hombre

no tienen fin. Sabemos que hubo un día

en que el pueblo de Dios buscaba el Nombre

en las vigilias de la judería.

No a la manera de otras que una vaga

sombra insinúan en la vaga historia,

aún está verde y viva la memoria

de Judá León, que era rabino en Praga.

Sediento de saber lo que Dios sabe,

Judá León se dió a permutaciones

de letras y a complejas variaciones

y al fin pronunció el Nombre que es la Clave,

la Puerta, el Eco, el Huésped y el Palacio,

sobre un muí±eco que con torpes manos

labró, para enseí±arle los arcanos

de las Letras, del Tiempo y del Espacio.

El simulacro alzó los soí±olientos

párpados y vio formas y colores

que no entendió, perdidos en rumores

y ensayó temerosos movimientos.

Gradualmente se vio (como nosotros)

aprisionado en esta red sonora

de Antes, Después, Ayer, Mientras, Ahora,

Derecha, Izquierda, Yo, Tú, Aquellos, Otros.

(El cabalista que ofició de numen

a la vasta criatura apodó Golem;

estas verdades las refiere Scholem

en un docto lugar de su volumen.)

El rabí le explicaba el universo

“esto es mi pie; esto el tuyo, esto la soga.”

y logró, al cabo de aí±os, que el perverso

barriera bien o mal la sinagoga.

Tal vez hubo un error en la grafía

o en la articulación del Sacro Nombre;

a pesar de tan alta hechicería,

no aprendió a hablar el aprendiz de hombre.

Sus ojos, menos de hombre que de perro

y harto menos de perro que de cosa,

seguían al rabí por la dudosa

penumbra de las piezas del encierro.

Algo anormal y tosco hubo en el Golem,

ya que a su paso el gato del rabino

se escondía. (Ese gato no está en Scholem

pero, a través del tiempo, lo adivino.)

Elevando a su Dios manos filiales,

las devociones de su Dios copiaba

o, estúpido y sonriente, se ahuecaba

en cóncavas zalemas orientales.

El rabí lo miraba con ternura

y con algún horror. ‘í¿Cómo’ (se dijo)

‘pude engendrar este penoso hijo

y la inacción dejé, que es la cordura?’

‘í¿Por qué di en agregar a la infinita

serie un símbolo más? í¿Por qué a la vana

madeja que en lo eterno se devana,

di otra causa, otro efecto y otra cuita?’

En la hora de angustia y de luz vaga,

en su Golem los ojos detenía.

í¿Quién nos dirá las cosas que sentía

Dios, al mirar a su rabino en Praga?

(Jorge Luis Borges, 1958)

In Jewish tradition, the golem is most widely known as an artificial creature created by magic, often to serve its creator. The word “golem” appears only once in the Bible (Psalms139:16). In Hebrew, “golem” stands for “shapeless mass.” The Talmud uses the word as “unformed” or “imperfect” and according to Talmudic legend, Adam is called “golem,” meaning “body without a soul” (Sanhedrin 38b) for the first 12 hours of his existence. The golem appears in other places in the Talmud as well. One legend says the prophet Jeremiah made a golem However, some mystics believe the creation of a golem has symbolic meaning only, like a spiritual experience following a religious rite.

The Sefer Yezirah (“Book of Creation”), often referred to as a guide to magical usage by some Western European Jews in the Middle Ages, contains instructions on how to make a golem. Several rabbis, in their commentaries on Sefer Yezirah have come up with different understandings of the directions on how to make a golem. Most versions include shaping the golem into a figure resembling a human being and using God’s name to bring him to life, since God is the ultimate creator of life..

According to one story, to make a golem come alive, one would shape it out of soil, and then walk or dance around it saying combination of letters from the alphabet and the secret name of God. To “kill” the golem, its creators would walk in the opposite direction saying and making the order of the words backwards.

Other sources say once the golem had been physically made one needed to write the letters aleph, mem, tav, which is emet and means “truth,” on the golem’s forehead and the golem would come alive. Erase the aleph and you are left with mem and tav, which is met, meaning “death.”

Another way to bring a golem to life was to write God’s name on parchment and stick it on the golem’s arm or in his mouth. One would remove it to stop the golem.

Often in Ashkenazi Hasidic lore, the golem would come to life and serve his creators by doing tasks assigned to him. The most well-known story of the golem is connected to Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the Maharal of Prague (1513-1609). It was said that he created a golem out of clay to protect the Jewish community from Blood Libel and to help out doing physical labor, since golems are very strong. Another version says it was close to Easter, in the spring of 1580 and a Jew-hating priest was trying to incite the Christians against the Jews. So the golem protected the community during the Easter season. Both versions recall the golem running amok and threatening innocent lives, so Rabbi Loew removed the Divine Name, rendering the golem lifeless. A separate account has the golem going mad and running away. Several sources attribute the story to Rabbi Elijah of Chelm, saying Rabbi Loew, one of the most outstanding Jewish scholars of the sixteenth century who wrote numerous books on Jewish law, philosophy, and morality, would have actually opposed the creation of a golem. (Source)

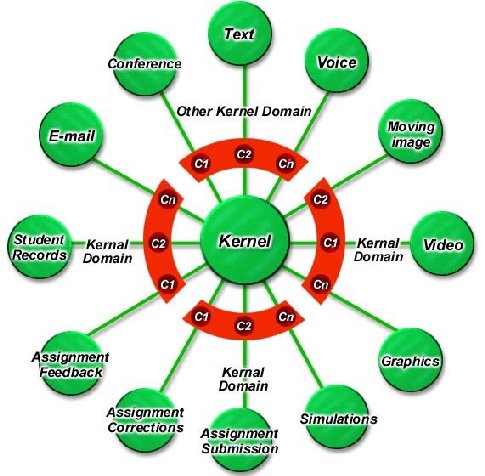

Kernel

Etymology: From Old English cyrnel, dimunitive of corn, seed

Pronunciation: * IPA: /Ã?Ë?kÃ?Å?ínÃ?â?¢l/ (UK) or /Ã?Ë?kínÃ?â?¢l/ (US)

1. The smallest, most basic piece of an object.

2. The very core, or center, of a larger system, upon which everything else is built.

3. (computing) The central part of many computer operating systems which manages the system’s resources and the communication between hardware and software components

4. A single seed, usually of corn.

5. The stone of certain fruits.

6. (mathematics) those elements, in the domain of a function, which the function maps to zero

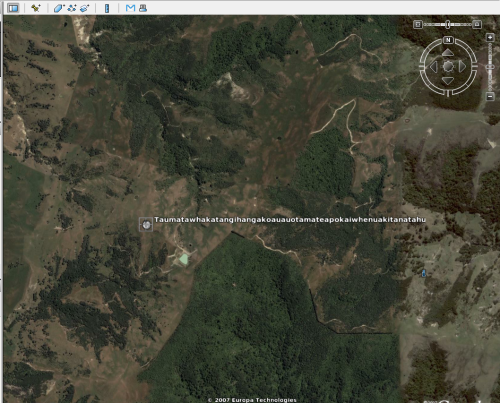

Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu

Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateapokaiwhenuakitanatahu, ou Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu é o nome maori para uma colina de 305 metros de altura próxima a Porangahau, sul de Waipukurau na região meridional da Baía de Hawke, Nova Zelândia. O nome é freqüentemente abreviado para Taumata pelos locais, para facilitar a conversação. O nome é í s vezes citado como sendo a palavra mais longa em inglês.

plaquinha indicativa

O nome escrito na placa que assinala a colina é Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu, o que, numa tradução literal seria algo como A testa [ou cume] da colina [ou lugar], onde Tamatea, o homem de joelhos grandes, que desceu, escalou e engoliu montanhas, [para viajar pela terra], que é conhecido como comedor de terra, tocou flauta nasal para sua amada. Com 85 letras, é um dos maiores nomes de lugares do mundo.

inspirado em bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnukwhikipedia

Cogito não Pára

Não deveríamos ter expectativa alguma do que fazemos, o que fazemos não é bom nem ruim, o que fazemos é nada. Os acontecimentos somente fazem parte de um coeficiente infinito: 0=0, pura redundância. Cúmplices de uma farsa, nossa lógica não é limpa, somos exorcizados a golpes inautênticos gerados pela cultura econômica dos excessos. Toda nova informação é formulada por uma expectativa frustrada, absoluta e que aponta para um único sentido/abismo.

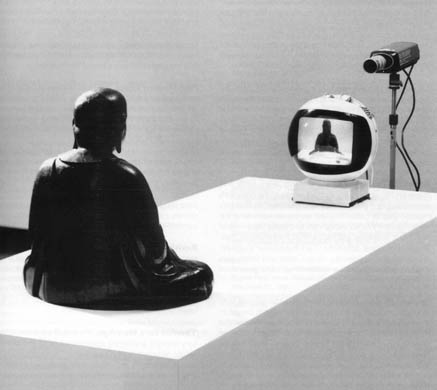

paik-buda

sala kernel programação

Desvio ou catástrofe? Delirium tremens. Ser o tormento dos próprios pensamentos, perturbação da nossa própria ordem. O desafio como ruído como desafio.

CONFUNDE A TI MESMO

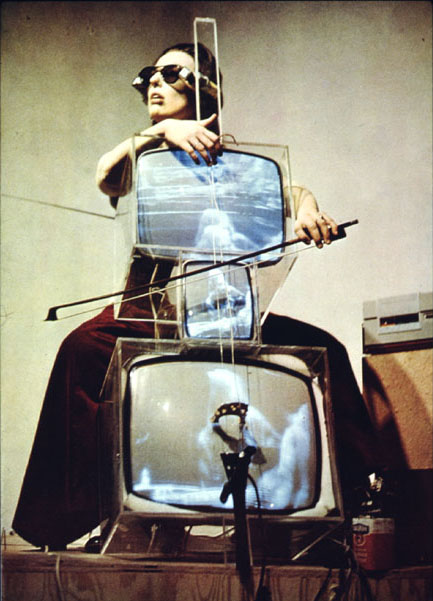

paik-violoncelista

It’s it! what is It?

CONFUNDORIENTA

nãofonia conSerto apresenta

Jean Baudrillard, o fotógrafo (27/07/1929 – 06/03/2007)

Entrevista com Jean Baudrillard – 1999

Sheila Leirner – Você está preparando muitas coisas ao mesmo tempo: um grande livro que vai ter a mesma importância de “L’Échange Symbolique et la Mort” de 1976, ou seja, vai amarrar toda a sua produção de lá para cá como um marco; traduz Hí¶lderlin; continua um último “Cool Memories” que começou em 1995 e termina no ano 2000. Qual é o lugar da fotografia no meio de toda essa produção?

Jean Baudrillard. – Tudo o que eu escrevi sobre a fotografia, a “troca impossível”, o vínculo com a imagem e o virtual, etc, juntei em vários lugares, como no “O Paroxista Indiferente” e em outros livros, como os de entrevistas”¦

S.L. – Desde 1991, essa deve ser a quarta conversa que nós fazemos para a mídia brasileira. Hoje, porém, nada de paroxista indiferente, guerra do Golfo, ilusão do fim, crimes perfeitos, complô da arte, confusões com a extrema direita. Gostaria que falássemos sobretudo sobre fotografia, sobre a sua fotografia que poucos conhecem. Há quanto tempo você fotografa?

J.B. – Oh!la!la! Já conversamos tudo isso? (Risadas)

Está bem, minha fotografia já tem uma década, mas ela se cristalizou melhor nos últimos dois ou três anos embora seja uma atividade paralela, pois os textos ficam sempre como ponto de fixação. Com a minha escritura eu faço uma coisa predestinada. Com a foto não. Quer dizer, pensando bem, até que sim”¦ Eu não poderia fazer pintura, escrever romances, rodar filmes. Antes eu exerci uma prática de política universitária e agora exerço algo imaterial, que é a prática da imagem”¦

S.L. – Imaterial ? Você diz que fotografar não é tomar o mundo como objeto, mas transformá-lo em objeto !

J.B. – Sim. Quero dizer imaterial, porém não para mim. A minha relação é com o objeto, as situações, a luz e a matéria. Trata-se de uma ligação que não é desencarnada, de certa forma é até carnal. A foto parte do mesmo núcleo que a escritura. A matriz é idêntica. No lugar de idéias, imagens.

S.L. – Antes você não pensava assim. Lembro-me que há alguns anos dizia não estabelecer nenhuma relação entre escrever e fotografar. E que se existia algo em comum era seguir essa coisa que está do outro lado do sujeito, perto do objeto, essa coisa irredutível, que tem uma ausência própria. Você não procurava captar a realidade dos objetos, não queria interpretá-los, decifrá-los”¦

J.B. – É verdade. Contudo, o que eu busco agora é tomar os objetos em sua literalidade, antes que comecem a “significar”. É um pouco como a linguagem poética que consegue existir antes de adquirir um sentido. Quando você escreve teoria, é difícil chegar lá pois o discurso tem sempre um significado. Mas í s vezes você entra numa linguagem quase poética, mesmo na teoria”¦

S.L. – A fotografia não seria para você uma espécie de “prova prática”, uma demonstração de tudo aquilo que você propõe em sua teoria?

J.B. – Não ! Isso não ! Demonstração não ! Não tenho nada a demonstrar.

S.L. – Uma prática dessa teoria ?

J.B. – Uma prática sim. Mas ela não é radical, pois se fosse não deveria nem mesmo ser estética. Eu próprio lastimo, mas acho as minhas fotos belas demais ! (Risadas). Tanto é que as melhores não são belas, as “melhores são as piores”, como se diz. Porém, a meu ver, ali é praticamente impossível chegar a alguma coisa que seja tão radical quanto as idéias que estão na cultura. O radicalismo da fotografia não está na idéia, está na literalidade. Nela, trata-se de encontrar um puro modo de aparição, enquanto que as idéias e a escritura constituem um modo de composição.

S.L. – Se na sua fotografia existe a tentativa de encontrar um puro modo de aparição, a escolha do sujeito não deveria importar. Porém, se “os objetos esperam que você os tome”, “que você os viole ‘sur place'”, como você diz, então porque só os objetos belos pedem essa violação? Porque as suas fotos nunca saem feias?

J.B. – Para mim não tem belo ou feio, mas eu também não vou pegar os objetos só porque eles são feios. Essa é a estética atual da feiúra, e eu não vou cair nela”¦ O que existe, e isso é importante, preste atenção, é a conjunção entre os objetos e uma finalidade técnica. Chegar í que a captação se faça quase como uma escrita automática. Agora, há uma escolha dos objetos, é claro”¦

S.L. – Uma escolha estética”¦

J.B. – Sim. Senão eu ficaria só fotografando aquela janela em frente da minha.

S.L. – Então existe um desejo seu. Não são os objetos que escolhem você, não são eles ” o sonham”, não “é o mundo que lhe reflete”, como você diz.

J.B. – Na verdade essa não é realmente uma escolha estética, é algo baseado na singularidade da imagem, da luz. Eu não sou a favor de fotografar tudo e qualquer coisa. Hoje em dia com a técnica de que se dispõe pode-se fazer ótimas fotos com o que se quiser. Eu não possuo talento técnico, procuro efetivamente algo de singular, um pouco como o “punctum” que Roland Barthes descreve.

S.L. – O “punctum” ou pontuação é a palavra que designa uma picada, uma marca, algo que vem ferir ou pungir o olhar. Os objetos que você escolhe talvez possuam para você esse “punctum”, mas o resultado de suas fotos é quase sempre indefectivelmente plástico.

J.B. – Você pode pegar objetos que já são estetizados, que são remarcáveis por sua própria qualidade estética. Ou você pode lhes impor uma estética, o que fazem hoje os fotógrafos. No meu caso, trata-se de escolher algo excepcional, porém não por meio de uma forma estética. É o objeto que me acena.

S.L. – Será que você fala de Barthes nesse ensaio “A Câmara Clara”, porque ele distingue a fotografia da arte fotográfica; e você, no fundo, rejeita a sua fotografia como arte ?

J.B. – Exatamente. Existem grandes fotógrafos, belas fotos que fazem parte da imensa maioria da arte fotográfica. Aqui não se trata de arte. Eu não sou um artista.

S.L. – Sempre a mesma história !

J.B. – Então não vale a pena repetir (Risadas).

S.L. – Você sempre diz que não é artista, mas toma os objetos em sua literalidade, em seu “punctum” que você descobre com a sua pura sensibilidade, e, como os poetas, tenta fazê-los existir antes que adquiram um sentido. Você sabe bem que a arte não é apenas uma questão de estética e a arte conceitual está aí para provar isso. Pois que só pensa pelos contrários, talvez você seja um artista apesar de você, não?

J.B. – As vezes essa é a melhor maneira de sê-lo (Risadas)! Mas, veja bem, como você diz, o livro de Barthes não é um livro de fotógrafo. Pode ser visto como um livro metafísico, de teoria, de um pensador. A foto o interessa tanto quanto o texto. Que prazer e paixão pode-se ter por uma imagem, e não apenas o prazer estético. Não é nem mesmo do nível do julgamento estético, pois o “punctum” está além dele, é uma forma de sedução instantânea. É um malentendido falar de sujeito e objeto nessas histórias. Mas é preciso pensar também que é um mito que nós possamos estar além do julgamento. Evidentemente existe sempre o julgamento, como existe sempre o discurso, como sempre existe uma escolha, uma afinidade”¦ é como nas relações pessoais. Mas não sou um artista. A minha jogada é muito mais da ordem do fatal do que do conceitual ou do estético.

S.L. – Depois a coisa pode entrar na historia da arte”¦

J.B. – Depois a coisa pode entrar na historia da arte, mas é uma outra existência. O “punctum” é uma matriz que escapa í toda categoria institucional enquanto ele existe, depois ele cai no mundo, na mundaneidade estética, e ninguém mais é responsável. Mas eu acho que existe um verdadeiro segredo onde as coisas aparecem e se produzem sozinhas, possuem uma forma de poder e de ilusão. A questão que atravessa o livro de Barthes é “onde está a realidade?”. O que você busca, por meio da imagem, é por em jogo essa realidade e verificar, paradoxalmente, que o mundo não é real. Há uma ilusão fundamental que é preciso conseguir captar. Depois, bem, a realidade existe também. Ela existe mas, sou agnóstico, não acredito nela.

S.L. – Porque não ?

J.B. – Se a realidade existe a gente não precisa acreditar nela. Pois se acreditarmos, ela torna-se um objeto de credo. E se for um credo, então deixa de ser uma realidade objetiva. Se ela é uma realidade objetiva, não precisa que nós acreditemos nela pois é objetiva. Porém, se você acreditar nela, ao contrário, você não a estará honrando como uma objetividade e ela passa a não existir mais. É como Deus, você entende? Se você começa a acreditar nele, ele não existe mais enquanto Deus. Torna-se um objeto de credo. E isso não O honra muito, pois na sua Existência Ele não tem nenhuma necessidade que as pessoas acreditem Nele. A única chance de a realidade existir é nós não acreditarmos nela”¦

S.L. – O fato é que vivemos sob um sistema de valores realistas. Veja o caso de Henri Cartier-Bresson, por exemplo. Há alguns anos, na conversa que tivemos para o Caderno 2, ele declarou que a fotografia é um pequeno “métier” e que o seu processo não o interessa, pois o que lhe importa é a vida e o meio imediato de transcrevê-la. O que você pensa disso?

J.B. – Eu só o encontrei umas duas ou três vezes. Ele tem consciência do seu gênio? É ansioso?

S.L. – Ele é terrivelmente mau-humorado. Não tem consciência disso como fotógrafo, mas tem ansiedade e pensa que possui gênio como pintor e desenhista, que é onde não possui gênio nenhum.

J.B. – (Risadas) Cartier-Bresson é uma lenda, um mito. Mas a sua fotografia não é a que mais me toca. É uma espécie de arte poético-realista de uma certa época”¦ uma bonita época que aliás teve o seu apogeu no cinema, mas não sei”¦ essa foto não é exatamente específica, ela é mais ou menos bela, mais ou menos bem sucedida, anedótica, descreve uma sociedade. É humanista, conta uma história, faz uma narrativa um pouco retrô. E parte do seu sucesso enorme é que se trata de um retrô.

S.L. – É que nós vivemos em termos de nostalgia estética”¦

J.B. – É. Mas estamos cheios de ver isso! Estamos cheios de ver esses dois meninos segurando esses dois litros de vinho, essas “obras-primas” ! (Risadas) Que, a meu ver não são nada grandiosas.

S.L. – Você pensa a mesma coisa de Sebastião Salgado?

J.B. – Não. Ele é admirável se quisermos, mas suscita o problema do voyeurismo sóciopolítico. A sua fotografia trata do humanismo da miserabilidade. Tudo isso me provoca um problema quase moral que não tenho vontade de resolver. É a foto-testemunho sobre a qual escrevi também algumas páginas. E aqui igualmente é preciso voltar a Barthes, pois o testemunho é o fim da fotografia. Ele inscreve uma idéia, uma verdade, ele não fotografa o que é, mas o que não deveria ser. Isso é uma posição moral de denegação. Se esta é uma foto moralizante, em relação í própria imagem ela é um contra-senso. Seria preciso que a imagem pudesse estar lá por sua especificidade e não curto-circuitada por uma idéia moralista, histórica”¦

S.L. – É uma imagem narrativa de quem, ao contrário de você, não é nada agnóstico com relação í realidade.

J.B. – É uma imagem usurpada. Há um abuso de imagem. Ela serve para exprimir algo, então é avassalada, não é imagem enquanto tal. Pode ser bela, mas é uma mistura de verdade, testemunho, moral e estética. Isso são valores que não me interessam. É a forma que conta. De todo modo, as fotos de Salgado são admiráveis pois tem uma bela composição, são esteticamente excelentes. São mundanas, no sentido em que a miséria do mundo também é mundana. Não devemos falar isso de forma demasiadamente brutal, senão nos tornamos cínicos, mas é preciso dizê-lo”¦

S.L. – Voltando a Cartier-Bresson, ele diz também que pode-se fazer qualquer coisa com uma máquina fotográfica, que só é difícil descascar uma batata com ela”¦

J.B. – (Risadas) Ele diz isso? Ele é engraçado ! Isso é verdade.

S.L. – Ele afirma ainda que todos são fotógrafos, que há tantos fotógrafos no mundo quanto aparelhos. Você concorda?

J.B. – Sim. Dá para ir ainda mais longe: dos livros sobre fotografia, há também o de Wilheim Flusser, nosso falecido amigo em comum que você convidou para as suas bienais. Flusser é bem mais radical que Cartier-Bresson. Ele diz que o fotógrafo não é senão o operador das possibilidades técnicas da máquina. É um pouco a reedição da fórmula Mac Luhan, “o meio é a mensagem”. Essa teoria é justa.

S.L. – Pensando bem, não ficou na lembrança muita coisa importante escrita sobre a fotografia. Tem você, Barthes, Susan Sontag, Flusser”¦

J.B. – É verdade. Mas você sabia que existe um texto fundamental de Italo Calvino sobre a fotografia que ninguém conhece, que se chama “A aventura de um fotógrafo” e que está num livro que se chama “Aventuras” ? Extraordinário ! Nem é preciso mais escrever sobre a fotografia pois tudo está lá. São dez páginas onde ele conta a história de alguém em seu processo de se tornar um fotógrafo. Esse personagem fotografa obsessivamente a sua amante em todas as posições, ela se cansa, o abandona, e ele começa a fotografar todos os objetos que estão lá no mesmo espaço. Contenta-se em fotografar eternamente tudo, e a história termina num delírio”¦

S.L. – Esse paroxismo o seduz ?

J.B. – É verdade que se estivermos possuídos pelo demônio da fotografia, a coisa termina num delírio, pois uma máquina técnica como essa é delirante em si, lhe dá todas as possibilidades e abre para a loucura!

S.L. – Essa loucura não está relacionada também com o tempo ? Segundo certos fotógrafos, mesmo os mais acadêmicos, existe uma angústia muito grande no delírio temporal. Ali, o presente concreto que pede para ser captado acontece numa fração de segundo, o que é desagradável e maravilhoso simultaneamente.

J.B. – É essa a diferença entre a fotografia e uma atividade estética como o desenho, por exemplo. O “punctum” não está apenas na idéia, está também no tempo. Quer dizer, existe um momento irreversível, imediatamente terminado e os fotógrafos têm razão.

S.L. – Muito embora você esteja no sentido inverso dos fotógrafos acadêmicos, que partem desse “instantâneo”, que é o “punctum” no tempo, para fazer uma obra pictórica e linear, que é oposta a ele”¦

J.B. – Sem dúvida. Para mim a fotografia não acontece senão sob a base da desaparição da vontade estética, apenas como objeto puro”¦

S.L. – Aí entra a questão da ficção. Uma vez que você toma o “objeto puro” como personagem “em via de aparição” num mundo em cuja realidade não acredita, você está criando uma ficção para que ele exista. Um cenário artificial, composto por meio da fotografia, para abrigar a sua existência. Isso me remete ao trabalho de fotógrafos como Miguel Rio Branco ou Cindy Sherman, que, sem serem acadêmicos, certamente partem da estética e da subjetividade para chegar í narração pictórica, í s vezes barroca, dessa realidade.

J.B. – Sim, mas isso é performance ! Nesse momento há um ciclo de atividades que é a construção de coisas e em seguida a representação delas. Eu não vejo onde está o momento original da foto lá dentro. Não é regra geral, mas se a foto consegue apagar o trabalho, fazer uma elipse sobre a construção e a demonstração do objeto, então ela volta a ser fotografia pura e simples. Eu não faço trucagem. Sempre existe um mergulho, uma escolha de luz, uma mis-en-scí¨ne subjetiva, mas eu os separo daquilo que vem de fora, eu mesmo venho de fora”¦ E acontece um encontro entre nós dois. Ao contrário de Rio Branco, não há nada de barroco no meu trabalho.

S.L. – Como é que você trabalha ?

J.B. – O meu método não tem nada a ver com o desses ficcionistas, mas também não tem relação com o de Cartier-Bresson. Eu tiro uma quantidade enorme de fotos e depois jogo fora o que não gosto. Quando fotografo, não controlo a situação e não quero controlá-la. Aí é um exercício completamente diferente da escritura. Gosto desse sentido aleatório da fotografia. Mas o importante é saber fazer a elipse. Toda a força da linguagem está nela.

S.L. – E se você tivesse que escolher um fotógrafo com quem sentisse uma afinidade ?

J.B. – Eu escolheria Luigi Ghirri ou Wim Wenders. Temos em comum não fotografar seres humanos. São universos hiper-realistas interessantes, mesmo que tenham se tornado um pouco estereotipados.

S.L. – Você não tem medo de também criar estereótipos com as suas fotos?

J.B. – Não! Não! Não vejo nada de comum entre minhas fotos. Estão todas numa espécie de desordem de cenas, objetos e ninguém jamais conseguiu encontrar um tema. Isso me deixa muito feliz! Não há personagens, rostos, sociologia, história, nada. Fiz a elipse máxima da coisa”¦ a ponto de me perguntar onde está a realidade lá dentro.

S.L. – Existe uma imagem difícil de esquecer que você inventou para a proliferação das obras de arte. Você disse que elas crescem como cogumelos cobrindo o mundo. Não fica assustado em pensar que as suas fotos e os seus textos se proliferam também?

J.B. – (Risadas) Sim, sim. Isso me incomoda. É porisso que eu pratico a “arte da desaparição”, ou seja, a arte de dosar homeopaticamente a existência dos objetos dos quais eliminei as minhas próprias pegadas. Quer dizer, você dá ao mundo objetos sublimes no sentido literal, que não pretendem nada, despojados ao máximo, e que são objetos de aparição/desaparição. Não são produzidos, construídos, não pertencem í s instituições em termos de significação, sentido, etc. Pratico uma arte de ilusionista, não sou produtor, criador ou artista. Tudo isso é uma superestrutura completamente paranóica. Por meio da elipse eu reduzo a realidade atravancada a tal ponto que chego í forma mínima. É a forma mais intensa, pois não tem uma existência representativa.

S.L. – Em que outros lugares encontramos formas parecidas a essas procuradas por você?

J.B. – Na música, por exemplo. Existem músicas que se dissipam. Elas não se impõem, elas se resolvem. Tudo se passa em termos de uma resolução perfeita. Não há resíduos, como os que encontramos nesse mundo do deteriorável. A música é um objeto que possui a magia de aparecer e desaparecer ao mesmo tempo. É preciso essas duas forças reversíveis, senão a sua obra fica como uma coisa produzida que atravanca a paisagem e se acumula em estoque. E há equivalentes desses objetos, vazios e ao mesmo tempo presentes, no texto ou na imagem.

S.L. – Sabemos o desgaste que sofreu a palavra revolucionário. No entanto, para terminar, se entendermos por ela a capacidade de mudar o sistema de valores, poderíamos dizer ainda que as suas estratégias no texto e na imagem são revolucionárias ?

J.B. – Eu não tento mudar o sistema de valores. O que eu pretendo é ficar fora do jogo e inventar uma outra regra para ele. Isso não é revolução, pois infelizmente não existe mais uma vontade política. Eu me coloco num universo paralelo, onde não há contradição violenta contra o sistema dominante, onde, mesmo que a minha posição o coloque em questão, não há nenhuma chance de revolucioná-lo na sua lógica. Estou na singularidade.

Ã?â?Ã?â??Ã?â?¢Ã?¨Ã?â? hi-j-ra ÇÃ?¬Ã?±é

The Digital Artisans Manifesto by Richard Barbrook and Pit Schultz

European Digital Artisans Network 1st May 1997

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

The Digital Artisans Manifesto

Making The Future

1. We are the digital artisans. We celebrate the Promethean power of our labour and imagination to shape the virtual world. By hacking, coding, designing and mixing, we build the wired future through our own efforts and inventiveness.

2. We are not the passive victims of uncontrollable market forces and technological changes. Without our daily work, there would be no goods or services to trade. Without our animating presence, information technologies would just be inert metal, plastic and silicon. Nothing can happen inside cyberspace without our creative labour. We are the only subjects of history.

3. The emergence of the Net signifies neither the final triumph of economic alienation nor the replacement of humanity by machines. On the contrary, the information revolution is the latest stage in the emancipatory project of modernity. History is nothing but the development of human freedom.

4. We will shape the new information technologies in our own interests. Although they were originally developed to reinforce hierarchical power, the full potential of the Net and computing can only be realised through our autonomous and creative labour. We will transform the machines of domination into the technologies of liberation.

5. We will contribute to the process of democratic emancipation. As digital artisans, we will come together to promote the development of our trade. As citizens, we will participate within republican politics. As Europeans, we will help to break down national and ethnic barriers both inside and outside of our continent.

The Present Moment

6. Freedom today is now often just the choice between commodities rather the ability to determine our own lives. Over the past two hundred years, the factory system has dramatically increased our material wealth at the cost of removing all meaningful participation in work. Even poorer members of European societies can now live better than the kings and aristocrats of earlier times. However the joys of consumerism are usually constrained by the boredom of most jobs.

7. Since 1968, the desire for increased monetary rewards has increasingly been supplemented by demands for increased autonomy at work. In the European Union and elsewhere, neo-liberals have tried to recuperate these aspirations through their policies of marketisation and privatisation. If we are talented workers in the ‘cutting-edge’ industries like hypermedia and computing, we are promised the possibility of becoming hip and rich entrepreneurs by the Californian ideologues. They want to recruit us as members of the ‘virtual class’ which seeks to dominate the hypermedia and computing industries.

8. Yet these neo-liberal panaceas provide no real solutions. Free market policies don’t just brutalise our societies and ignore environmental degradation. Above all, they cannot remove alienation within the workplace. Under neo- liberalism, individuals are only allowed to exercise their own autonomy in deal-making rather than through making things. We cannot express ourselves directly by constructing useful and beautiful virtual artifacts.

9. For those of us who want to be truly creative in hypermedia and computing, the only practical solution is to become digital artisans. The rapid spread of personal computing and now the Net are the technological expressions of this desire for autonomous work. Escaping from the petty controls of the shopfloor and the office, we can rediscover the individual independence enjoyed by craftspeople during proto-industrialism. We rejoice in the privilege of becoming digital artisans.

10. We create virtual artifacts for money and for fun. We work both in the money-commodity economy and in the gift economy of the Net. When we take a contract, we are happy to earn enough to pay for our necessities and luxuries through our labours as digital artisans. At the same time, we also enjoy exercising our abilities for our own amusement and for the wider community. Whether working for money or for fun, we always take pride in our craft skills. We take pleasure in pushing the cultural and technical limits as far forward as possible. We are the pioneers of the modern.

11. The revival of artisanship is not a return to a low-tech and impoverished past. Skilled workers are best able to assert their autonomy precisely within the most technologically advanced industries. The new artisans are better educated and can earn much more money. In earlier stages of modernity, factory labourers symbolised of the promise of industrialism. Today, as digital artisans, we now express the emancipatory potential of the information age. We are the promise of history.

12. We not only admire the individualism of our artisan forebears, but also we will learn from their sociability. We are not petit-bourgeois egoists. We live within the highly collective institutions of the market and the state. For many people, autonomy over their working lives has often also involved accepting the insecurity of short- term contracts and the withdrawal of welfare provisions. We can only mitigate these problems through our own collective action. As digital artisans, we need to come together to promote our common interests.

13. We believe that digital artisans within this continent now need to form their own craft organisation. In early modernity, artisans enhanced their individual autonomy by organising themselves into trade associations. We proclaim that the collective expression of our trade will be: the European Digital Artisans Network (EDAN).

The Aims of EDAN

14. We urge everyone who is working within hypermedia, computing and associated professions on this continent to join EDAN. We call on digital artisans to form branches of the network in each of the member states of the European Union and its associated countries. By forming EDAN, we will also be creating a means of forging links between European digital artisans and those from elsewhere in the world. We will strive for cooperation in work and in play with our fellow artisans in all countries.

15. We believe that the principal task of EDAN is to enhance the exercise of our craft skills. By collaborating together, we can protect ourselves against those who wish to impose their self- interests upon us. By having a strong collective identity, we will enjoy more individual autonomy over our own working lives.

16. EDAN will celebrate our creative genius as digital artisans. The network will act as the collective memory about the achievements of digital artisans within Europe. It will publicise outstanding ‘masterpieces’ of craft skill made by its members among the trade and to the wider public.

17. The network will be the social meeting-place for digital artisans from across Europe. EDAN will organise festivals, conferences and congresses where we can meet to organise, discuss and party. We believe that digital artisans should express their collective identity by regularly celebrating together in private and public.

18. EDAN will collect detailed knowledge about the trade in the different regions of Europe. It will aim to provide information about best practice in contracts, copyright agreements and other business arrangements to its members. The network will also be a source of contacts in each locality for digital artisans looking for work in different areas of Europe.

19. We believe that what cannot be organised by our own autonomous efforts can only be provided through democratic political institutions. The network will lobby for changes in local, national and European legislation which can enhance our working lives as digital artisans. As concerned citizens, we will also support the fullest development of public welfare services.

20. EDAN will campaign for European governments to put more resources into the theoretical and practical education of digital artisans in schools and universities. The network will facilitate links between educational institutions teaching hypermedia and computing across the continent. EDAN also believes that publicly-funded research is necessary for the fullest development of our industry.

21. EDAN will urge the European Union to launch a public works programme to build a broadband fibre- optic network linking all households and businesses. We believe in the principle of universal service: everyone should have Net access at the cheapest possible price. No society can call itself truly democratic until all citizens can directly exercise their right to media freedom over the Net.

22. We will campaign for the creation of ‘electronic public libraries’ where on-line educational and cultural resources are made accessible to everyone for free. Public investment in digital methods of delivering life-long learning is needed to create an information society. The Net should become the encyclopedia of all knowledge: the primary resource for the new Enlightenment.

23. We believe that the role of the hi-tech gift economy should be further enhanced. As the history of the Net has shown, d.i.y. culture is now an essential part of the process of social development. Without hacking, piracy, shareware and open architecture systems, the limitations of the money-commodity economy would have prevented the construction of the Net. EDAN also supports open access as means of people beginning to learn the skills of hypermedia and computing. The promotion of d.i.y. culture within the Net is now a precondition for the successful construction of cyberspace.

24. We are the digital artisans. We are building the information society of the future. We have come together to advance our collective interests and those of our fellow citizens. We are organised as the European Network of Digital Artisans. Join us.

Digital Artisans of Europe Unite!

Of Brains & Walnuts

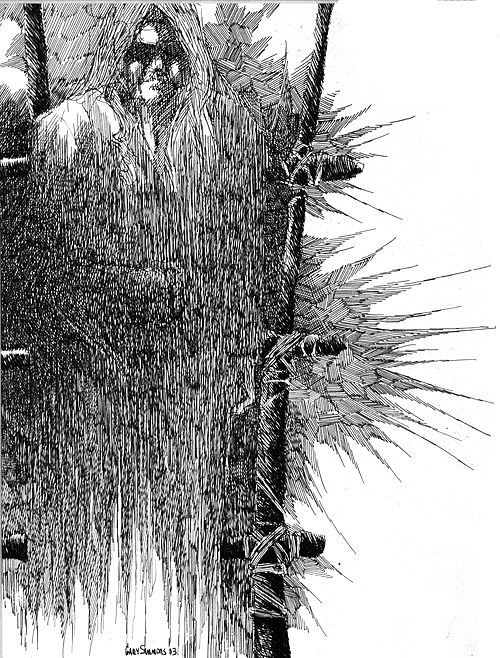

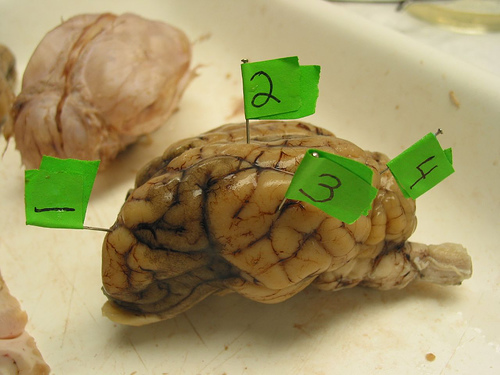

“Brain surgery” (photo by Ilona Angervuo).

Philosophy and the habits of Critical Thinking

Conversation with John Searle

Philosophical Problems

Is it hard to do philosophy?

It’s murder, absolutely. I compare it … if you really want to know how to do it, you get up in the morning, there’s a large brick wall and you run your head against that brick wall. And you keep doing that every day until eventually you make a hole in the wall. That’s what it feels like.

But metaphorically the wall has ceased to exist, right? Using the metaphor that you’re always …

Unfortunately I keep banging the wall. And then once I get one wall battered into shape then I’ve got to work on another one. Now the way it actually works out is that you’re constantly fighting with a whole lot of apparently contradictory ideas, and yet they all seem appealing and you have to find some way to resolve them.

So take an obvious case. We’re all conscious and it’s real. All you do is pinch yourself and you know this is real. How can matter be conscious? You know, what you’ve got in your skull is about a kilogram and a half, three pounds of this gook. It’s about the texture of English oatmeal — it’s slimier. And it’s gray and white. And now how can this three pounds of gook in your skull, how can that have all these thoughts and feelings and anxieties and aspirations? How can all of the variety of our conscious life be produced by this squishy stuff blasting away at the synapses? A hundred billion neurons, glial cells, synapses, how does that produce consciousness? And that’s typical of philosophical problems. On the one had you want to say, well, consciousness couldn’t exist because, you know, how does it fit in with the physical world? On the other hand we all know it does exist, so you have to find some way to resolve that. That’s a typical philosophical problem.

And this has been a major research interest of yours in philosophy.

Well, this one right now is, yes. In my early career I worked on language. My main research was about language and speech. My first two books were about the philosophy of language. But when I was writing those books I kept using mental notions like belief and intention and desire and human action. And I knew some day I’d have to pay off that debt, I’d have to go and write a book about those sorts of things. So I did. I wrote a book called Intentionality. But that left open this whole range of traditional issues in the philosophy of mind. How does the mind work? How does it relate to physical reality? I’ve written several books about those issues. And two things happened. One is, consciousness became a fashionable subject. For the first twenty or thirty years of my career, if you talked about consciousness people thought you’re some kind of mystic or you’re not serious. But that’s changed now. Now it’s a very exciting subject. And the second thing that happened was that cognitive science was created as a new discipline and I was in on that. It was in the late seventies and early eighties that here in Berkeley, and really all over the country, we created this new movement of cognitive science.

As a philosophical issue, what is really exciting about this is that it touches on this whole division between the mind and the body, which is something that philosophy has never really resolved.

That’s why I’m trying to resolve it. What I’m trying to say is we need to get rid of the seventeenth-century categories.

“Getting centred” (photo by BidWiya)

We’ve inherited this vocabulary that makes it look as if mental and physical name different realms. And it’s part of our popular culture, so we sing songs about your body and your soul or we have saying about how your mind is willing but your flesh is weak, and sometimes the other way around, the flesh is willing but the mind is weak. And we have inherited, not only philosophically but in our religious tradition, we’ve inherited the idea that there are two quite distinct realms, a realm of the spiritual and a realm of the physical. And I’m fighting against that. I want to say we live in one realm, it’s got all of these features, and once you see that then the philosophical mind-body problem dissolves. You’re still left with a terrible problem in neurobiology, namely, how does the brain do it, in detail? What are the specific neurotransmitters? What’s the neuronal architecture? But I think the philosophical problem, how is it possible that the mental can be a real part of a world that’s entirely physical, I think that problem I can solve.

And how?

The way I solve it is to get rid of the traditional categories. Forget about Descartes’s categories of res existence and res cogitance, that is, the extended reality of the material and the thinking reality of the mental. Once you get rid of the categories and you ask yourself how it works, then it seems to me there are two principles which, if properly understood (it’s not all that easy to understand them, but if properly understood –) provide you with a solution to the traditional mind-body problem. Those principles are first, all of our mental processes are caused by lower-level neuronal processes in the brain. We assume that it’s at the level of neurons, but that’s for the specialists to settle in the end. Neurons and synapses — maybe you’ve got to go higher, maybe you’ve got to go lower — but some sorts of lower-level processes in the brain, whether it’s clusters of neurons or subneuronal parts or neurons and synapses, their behavior causes all of your mental life. Everything from feeling pains and tickles and itches, pick your favorite, to suffering the angst of post-industrial man under late capitalism, whatever is your favorite.

Or stubbing your toe.

Or stubbing your toe. Whatever is your favorite feeling. Feeling ecstatic at a football game, feeling drunk when you’ve had too much to drink. All of that is caused by variable rates of neuron firings in the brain or some other such neurobiological phenomenon, we don’t know in detail what. Okay, that’s principle number one. Brains cause minds. All of our mental life is causally explained by the behavior of neuronal systems.

The second principle is just as important: the mental reality which is caused by the neurobiological phenomena is not a separate substance that’s squirted out. It isn’t some kind of juice that’s squirted out by the neurons. It’s just the state that the system is in. That is to say, the behavior of the microelements causes a feature of the entire system at a macro level, even though the system is made up entirely of those elements that cause the higher level behavior. Now that’s hard for most people to grasp, that you can accept both that the relation between the brain and the mind is causal, and that the mind is just a feature of the brain. But if you think about it, nature is full of stuff like that.

Look at this glass of water, for example. It’s liquid. Now, liquidity is a real feature, but the liquidity is explained by the behavior of the molecules, that is, the liquid behavior is explained by the behavior of the molecules, even though the liquidity is just a feature of the whole system of molecules. I can’t find a single molecule and say “This one is liquid, this one is wet, I’ll see if I can find you a dry one.” Similarly, I can’t find a single neuron and say “This one is conscious or this one is unconscious.” We’re talking about features of whole systems that are explained by the behavior of the microelements of those systems. So I think the philosophical problem is resolved. That is, I don’t have any worry about the philosophical mind-body problem. But the scientific problem — how exactly does the machinery do it? — that’s still very much up for grabs. And I’m in the middle of that battle as well, even though I’m not a neuroscientist. Okay, there are a whole lot of other philosophical problems left over, book cover but that one I’m not worried about.

In one of your most recent books you talk in passing throughout the book about doing philosophy, that’s my interpretation; but at one point you say “It’s always good to remind ourselves of the facts.” You’ve said this is really exciting, and part of the excitement comes from doing this [philosophical] work at the same time that all these biological discoveries are being made.

That’s right. You see, I think in philosophy especially you have to remind yourself of what you know already. We know that the world is made up of entities that we call particles. They’re not exactly particles but that’s close enough. It’s made up of entities, molecules, atoms, sub-atomic particles. It’s made up of these tiny entities and they’re organized into systems. And these systems have causal relations to other systems. So a planet is a system and a water molecule is a system. A baby is a system. There are all these subsystems. And some of those systems have evolved through biological evolution.

We’re carbon-based systems with a heavy dosage of hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen. That’s our life. We’ve got a thing about these four elements. And those systems evolve across evolutionary time. We know all of that. Now some of those carbon-based, living systems have evolved neuronal systems. Funny kind of cell, the neuron. It’s a cell like any other, but it’s different anatomically. And some of those neuronal systems cause consciousness. Start there. Now that’s how much we know before the philosopher ever goes to work. Then we go to work on that. We don’t go back and think, well, maybe the real world doesn’t exist. No, that’s not an option. So you have to remind yourself of what you actually know.

At one point you’re trying to explain when we do philosophy. This is in … I can’t remember which book this was in, but you say, “As soon as we are confident that we really have knowledge and understanding in some domain, we stop calling it philosophy and start calling it science. And as soon as we make some definite progress, we think ourselves entitled to call it scientific progress.”

That’s right, yes.

So this world you’re in right now, that’s part of the excitement, right?

That’s right. What happens is this.