Knowledge and will

As discussed in sections knowledge and will, we understand knowledge as a model, or recursive generator of predictions; while will is that agency which selects, or resolves uncertainty, in systemic processes. Knowledge and will are intimately related in the actions of all neural systems: the availability of knowledge acts as an a priori constraint on the range of possible actions; while the will selects a final action from that set.

In our thought and language we distinguish two different classes of elements which we say exist: our beliefs, expressing what we think we know; and our desires or intentions, expressing what we are striving for and intend to do. We can describe the elements of the first class collectively as knowledge, and the elements of the second class as will. They are not isolated from each other. Our goals and even our wishes depend on what we know about our environment. Yet they are not determined by it in a unique way. We clearly distinguish between the range of options we have and the actual act of choosing between them. As an American philosopher noticed, no matter how carefully you examine the schedule of trains, you will not find there an indication as to where you want to go. We think about knowledge as a representation of the world in our mind.

Another way to describe the relation between knowledge and will is as a dichotomy between not-I and I, or between object and subject. The border between them is defined by the phrase “I can”. Indeed, the content of our knowledge is independent of our will in the sense that we cannot change it by simply changing our intentions or preferences. On the contrary, we can change our intentions without any externally observable actions. We call it our will. It is the essence of our “I”.

Source: Principia Cybernetica

ON SLEEP AND SLEEPLESSNESS

Aristotle (350 BC)

WITH regard to sleep and waking, we must consider what they are:

whether they are peculiar to soul or to body, or common to both; and

if common, to what part of soul or body they appertain: further,

from what cause it arises that they are attributes of animals, and

whether all animals share in them both, or some partake of the one

only, others of the other only, or some partake of neither and some of

both.

Further, in addition to these questions, we must also inquire what

the dream is, and from what cause sleepers sometimes dream, and

sometimes do not; or whether the truth is that sleepers always dream

but do not always remember (their dream); and if this occurs, what its

explanation is.

Again, [we must inquire] whether it is possible or not to foresee

the future (in dreams), and if it be possible, in what manner;

further, whether, supposing it possible, it extends only to things

to be accomplished by the agency of Man, or to those also of which the

cause lies in supra-human agency, and which result from the workings

of Nature, or of Spontaneity.

Cuidados com seu pitbull

Uma boa caminhada é um exercício bem gostoso para o cão, deixar ele cheirar e fazer xixí faz parte do processo, o passeio deve ser agradável ao cãozinho, importante estar em ordem com a vacina, particularmente aconselho reservar o filhote até completar a carteira de vacinas e só depois apresentar o passeio na rua, pois o fato de cheirar as fezes de animais adultos e/ou doentes pode conter encubadas viroses e até desenvolver no animalzinho com saúde ainda vulnerável.

Que tipo de exercícios devo fazer com meu pit bull?

Todos! Corrida e natação são muito interessantes. Outra coisa que eles adoram é o bungle jump, um objeto qualquer no qual eles possam se pendurar pela boca. Isto nada tem a ver com treinamento para rinhas ou aumento da agressividade do cão. Ao contrário. O pit bull é um cão de alto prey drive e o bungle jump é uma boa válvula de descarga.

What Is the Soul?

Bertrand Russell, 1928.

One of the most painful circumstances of recent advances in science is that each one makes us know less than we thought we did. When I was young we all knew, or thought we knew, that a man consists of a soul and a body; that the body is in time and space, but the soul is in time only. Whether the soul survives death was a matter as to which opinions might differ, but that there is a soul was thought to be indubitable. As for the body, the plain man of course considered its existence self-evident, and so did the man of science, but the philosopher was apt to analyse it away after one fashion or another, reducing it usually to ideas in the mind of the man who had the body and anybody else who happened to notice him. The philosopher, however, was not taken seriously, and science remained comfortably materialistic, even in the hands of quite orthodox scientists.

Nowadays these fine old simplicities are lost: physicists assure us that there is no such thing as matter, and psychologists assure us that there is no such thing as mind. This is an unprecedented occurrence. Who ever heard of a cobbler saying that there was no such thing as boots, or a tailor maintaining that all men are really naked? Yet that would have been no odder than what physicists and certain psychologists have been doing. To begin with the latter, some of them attempt to reduce everything that seems to be mental activity to an activity of the body. There are, however, various difficulties in the way of reducing mental activity to physical activity. I do not think we can yet say with any assurance whether these difficulties are or are not insuperable. What we can say, on the basis of physics itself, is that what we have hitherto called our body is really an elaborate scientific construction not corresponding to any physical reality. The modern would-be materialist thus finds himself in a curious position, for, while he may with a certain degree of success reduce the activities of the mind to those of the body, he cannot explain away the fact that the body itself is merely a convenient concept invented by the mind. We find ourselves thus going round and round in a circle: mind is an emanation of body, and body is an invention of mind. Evidently this cannot be quite right, and we have to look for something that is neither mind nor body, out which both can spring.

Let us begin with the body. The plain man thinks that material objects must certainly exist, since they are evident to the senses. Whatever else may be doubted, it is certain that anything you can bump into must be real; this is the plain man’s metaphysic. This is all very well, but the physicist comes along and shows that you never bump into anything: even when you run your hand along a stone wall, you do not really touch it. When you think you touch a thing, there are certain electrons and protons, forming part of your body, which are attracted and repelled by certain electrons and protons in the thing you think you are touching, but there is no actual contact. The electrons and protons in your body, becoming agitated by nearness to the other electrons and protons are disturbed, and transmit a disturbance along your nerves to the brain; the effect in the brain is what is necessary to your sensation of contact, and by suitable experiments this sensation can be made quite deceptive. The electrons and protons themselves, however, are only crude first approximations, a way of collecting into a bundle either trains of waves or the statistical probabilities of various different kinds of events. Thus matter has become altogether too ghostly to be used as an adequate stick with which to beat the mind. Matter in motion, which used to seem so unquestionable, turns out to be a concept quite inadequate for the needs of physics.

Nevertheless modern science gives no indication whatever of the existence of the soul or mind as an entity; indeed the reasons for disbelieving in it are very much of the same kind as the reasons for disbelieving in matter. Mind and matter were something like the lion and the unicorn fighting for the crown; the end of the battle is not the victory of one or the other, but the discovery that both are only heraldic inventions. The world consists of events, not of things that endure for a long time and have changing properties. Events can be collected into groups by their causal relations. If the causal relations are of one sort, the resulting group of events may be called a physical object, and if the causal relations are of another sort, the resulting group may be called a mind. Any event that occurs inside a man’s head will belong to groups of both kinds;

Well, maybe not any event; to take drastic example, being shot in the head.

considered as belonging to a group of one kind, it is a constituent of his brain, and considered as belonging to a group of the other kind, it is a constituent of his mind.

Thus both mind and matter are merely convenient ways of organizing events. There can be no reason for supposing that either a piece of mind or a piece of matter is immortal. The sun is supposed to be losing matter at the rate of millions of tons a minute. The most essential characteristic of mind is memory, and there is no reason whatever to suppose that the memory associated with a given person survives that person’s death. Indeed there is every reason to think the opposite, for memory is clearly connected with a certain kind of brain structure, and since this structure decays at death, there is every reason to suppose that memory also must cease. Although metaphysical materialism cannot be considered true, yet emotionally the world is pretty much the same as it would be if the materialists were in the right. I think the opponents of materialism have always been actuated by two main desires: the first to prove that the mind is immortal, and the second to prove that the ultimate power in the universe is mental rather than physical. In both these respects, I think the materialists were in the right. Our desires, it is true, have considerable power on the earth’s surface; the greater part of the land on this planet has a quite different aspect from that which it would have if men had not utilized it to extract food and wealth. But our power is very strictly limited. We cannot at present do anything whatever to the sun or moon or even to the interior of the earth, and there is not the faintest reason to suppose that what happens in regions to which our power does not extend has any mental causes. That is to say, to put the matter in a nutshell, there is no reason to think that except on the earth’s surface anything happens because somebody wishes it to happen. And since our power on the earth’s surface is entirely dependent upon the sun, we could hardly realize any of our wishes if the sun grew could. It is of course rash to dogmatize as to what science may achieve in the future. We may learn to prolong human existence longer than now seems possible, but if there is any truth in modern physics, more particularly in the second law of thermodynamics, we cannot hope that the human race will continue for ever. Some people may find this conclusion gloomy, but if we are honest with ourselves, we shall have to admit that what is going to happen many millions of years hence has no very great emotional interest for us here and now. And science, while it diminishes our cosmic pretensions, enormously increases our terrestrial comfort. That is why, in spite of the horror of the theologians, science has on the whole been tolerated.

The universe is a labyrinth made of labyrinths. Each leads to another.

And wherever we cannot go ourselves, we reach with mathematics.

— Stanislaw Lem, Fiasco

“Ce que cââ?¬â?¢est que penser.

Par le mot de penser, jââ?¬â?¢entends tout ce qui se fait en nous de telle sorte que nous lââ?¬â?¢apercevons immédiatement par nous-mêmes ; cââ?¬â?¢est pourquoi non seulement entendre, vouloir, imaginer, mais aussi sentir est la même chose ici que penser.” Article 9 des Principes de la philosophie.

” Par le nom de pensée, je comprends tout ce qui est tellement en nous que nous en sommes immédiatement connaissants “ Réponses aux secondes objections.

” Il nââ?¬â?¢y a aucune pensée de laquelle, dans le moment quââ?¬â?¢elle est en nous, nous nââ?¬â?¢ayons une actuelle connaissance. “ Réponses aux sixií¨mes objections.

René Descartes

“Trente rayons convergent au moyeu

Mais c’est le vide médian qui fait marcher le char”

Lao Tsé – Tao to king

I want to block some common misunderstandings about “understanding”: In many of these discussions one finds a lot of fancy footwork about the word “understanding.

(…)

I will argue that in the literal sense the programmed computer understands what the car and the adding machine understand, namely, exactly nothing.

(…)

In many cases it is a matter for decision and not a simple matter of fact whether x understands y; and so on.

(…)

My car and my adding machine understand nothing: they are not in that line of business.

(…)

Newell and Simon (1963) write that the kind of cognition they claim for computers is exactly the same as for human beings. I like the straightforwardness of this claim, and it is the sort of claim I will be considering.

(…)

Our tools are extensions of our purposes, and so we find it natural to make metaphorical attributions of intentionality to them; but I take it no philosophical ice is cut by such examples.

(…)

The sense in which an automatic door “understands instructions” from its photoelectric cell is not at all the sense in which I understand English.

(…)

There are clear cases in which “understanding” literally applies and clear cases in which it does not apply; and these two sorts of cases are all I need for this argument.

(…)

To all of these points I want to say: of course, of course. But they have nothing to do with the points at issue.

(…)

We often attribute “understanding” and other cognitive predicates by metaphor and analogy to cars, adding machines, and other artifacts, but nothing is proved by such attributions.

John Searle

I am the Walrus

(Lennon/McCartney)

I am he as you are he as you are me

and we are all together

See how they run like pigs from a gun

see how they fly

I’m crying

Sitting on a cornflake

Waiting for the van to come

Corporation T-shirt, stupid bloody Tuesday

Man you’ve been a naughty boy

you let your face grow long

I am the eggman

they are the eggmen

I am the walrus

Goo goo g’ joob

Mr. city policeman sitting

pretty little policemen in a row

See how they fly like Lucy in the sky

See how they run

I’m crying

I’m crying, I’m crying

Yellow matter custard

Dripping from a dead dog’s eye

Crabalocker fishwife

Pornographic priestess

Boy, you’ve been a naughty girl

you let your knickers down

I am the eggman

They are the eggmen

I am the walrus

Goo goo g’ joob

Sitting in an English garden

waiting for the sun

If the sun don’t come you get a tan

from standing in the English rain

I am the eggman

They are the eggmen

I am the walrus

Goo goo g’ joob

Expert, texpert choking smokers

don’t you think the joker laughs at you

See how they smile like pigs in a sty

See how they snide

I’m crying

Semolina pilchard

climbing up the Eiffel tower

Elementary penguin singing Hare Krishna

Man, you should have seen them kicking

Edgar Allan Poe

I am the eggman

They are the eggmen

I am the walrus

Goo goo g’ joob

Goo goo g’ joob

Goo goo g’ goo

goo goo g’ joob goo

juba juba juba

juba juba juba

juba juba juba juba

juba juba

Education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten.

(…)

I did not direct my life. I didn’t design it. I never made decisions. Things always came up and made them for me. That’s what life is.

(…)

Society attacks early, when the individual is helpless.

(…)

The real problem is not whether machines think but whether men do.

(…)

We shouldn’t teach great books; we should teach a love of reading.

B. F. Skinner

George Orwell, 1984, Chapter 6

(…)

A shrill trumpet-call had pierced the air. It was the bulletin! Victory! It always meant victory when a trumpet-call preceded the news. A sort of electric drill ran through the cafe. Even the waiters had started and pricked up their ears.

The trumpet-call had let loose an enormous volume of noise. Already an excited voice was gabbling from the telescreen, but even as it started it was almost drowned by a roar of cheering from outside. The news had run round the streets like magic. He could hear just enough of what was issuing from the telescreen to realize that it had all happened, as he had foreseen; a vast seaborne armada had secretly assembled a sudden blow in the enemy’s rear, the white arrow tearing across the tail of the black. Fragments of triumphant phrases pushed themselves through the din: ‘Vast strategic manoeuvre — perfect co-ordination — utter rout — half a million prisoners — complete demoralization — control of the whole of Africa — bring the war within measurable distance of its end victory — greatest victory in human history — victory, victory, victory!’

Under the table Winston’s feet made convulsive movements. He had not stirred from his seat, but in his mind he was running, swiftly running, he was with the crowds outside, cheering himself deaf. He looked up again at the portrait of Big Brother. The colossus that bestrode the world! The rock against which the hordes of Asia dashed themselves in vain! He thought how ten minutes ago — yes, only ten minutes — there had still been equivocation in his heart as he wondered whether the news from the front would be of victory or defeat. Ah, it was more than a Eurasian army that had perished! Much had changed in him since that first day in the Ministry of Love, but the final, indispensable, healing change had never happened, until this moment.

The voice from the telescreen was still pouring forth its tale of prisoners and booty and slaughter, but the shouting outside had died down a little. The waiters were turning back to their work. One of them approached with the gin bottle. Winston, sitting in a blissful dream, paid no attention as his glass was filled up. He was not running or cheering any longer. He was back in the Ministry of Love, with everything forgiven, his soul white as snow. He was in the public dock, confessing everything, implicating everybody. He was walking down the white-tiled corridor, with the feeling of walking in sunlight, and an armed guard at his back. The longhoped-for bullet was entering his brain.

He gazed up at the enormous face. Forty years it had taken him to learn what kind of smile was hidden beneath the dark moustache. O cruel, needless misunderstanding! O stubborn, self-willed exile from the loving breast! Two gin-scented tears trickled down the sides of his nose.

But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished.

He had won the victory over himself.

He loved Big Brother.

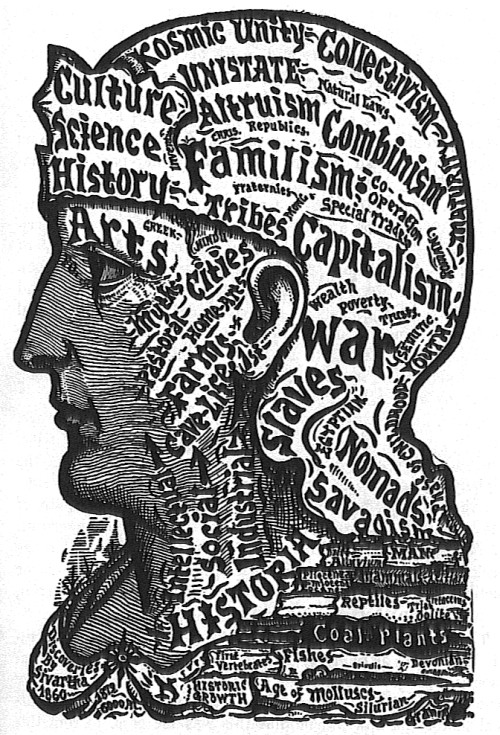

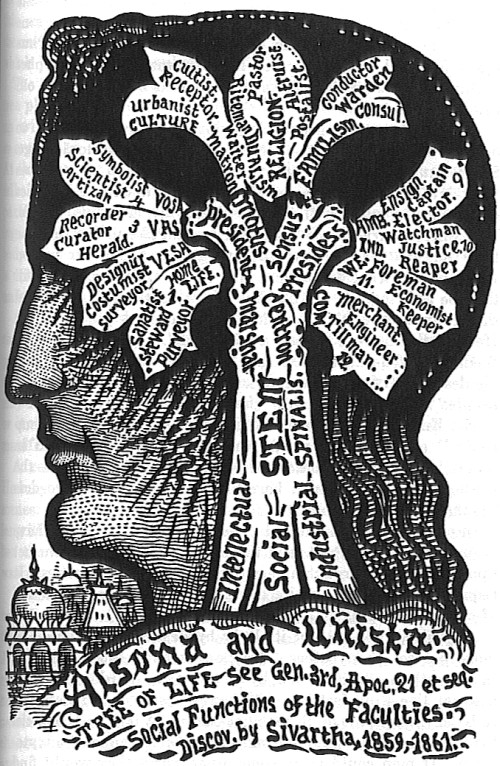

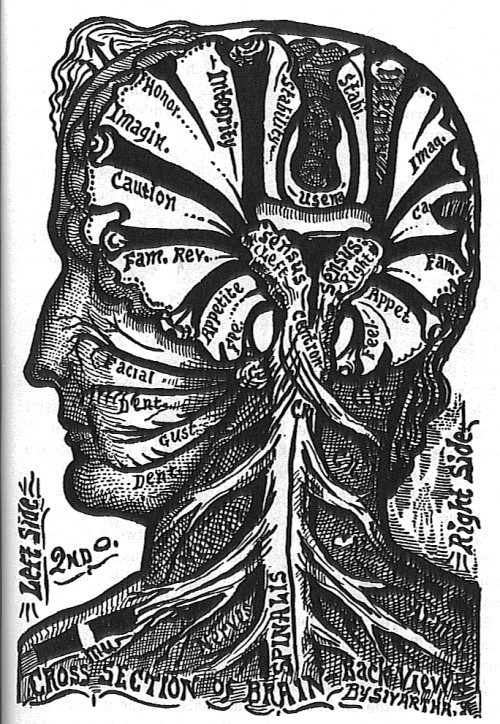

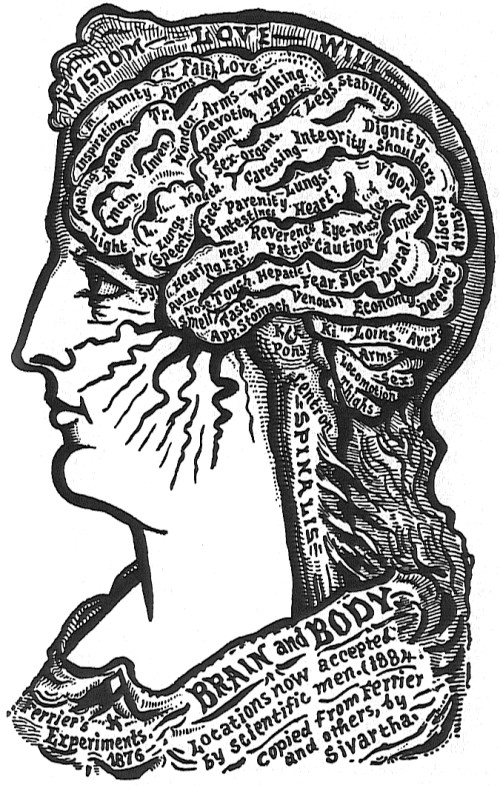

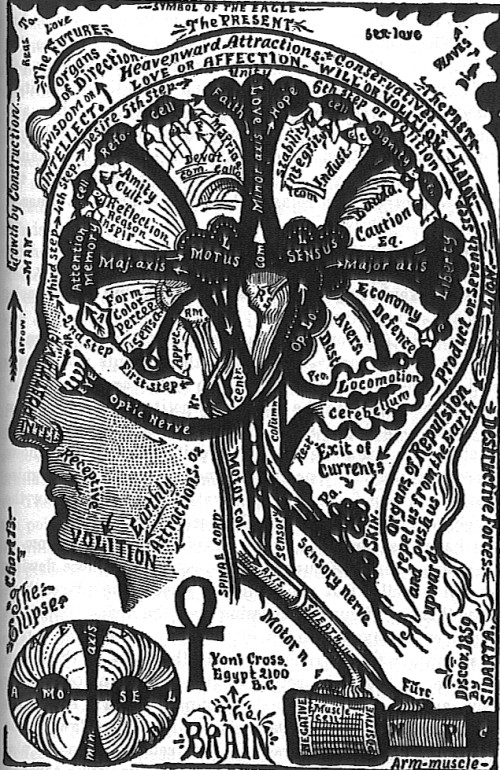

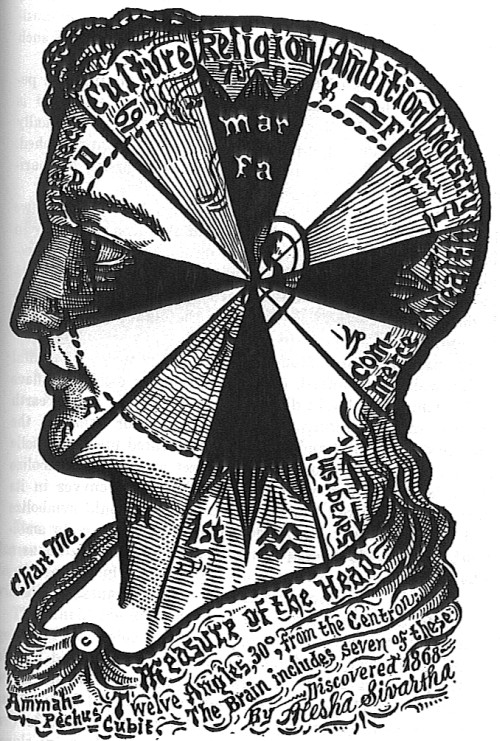

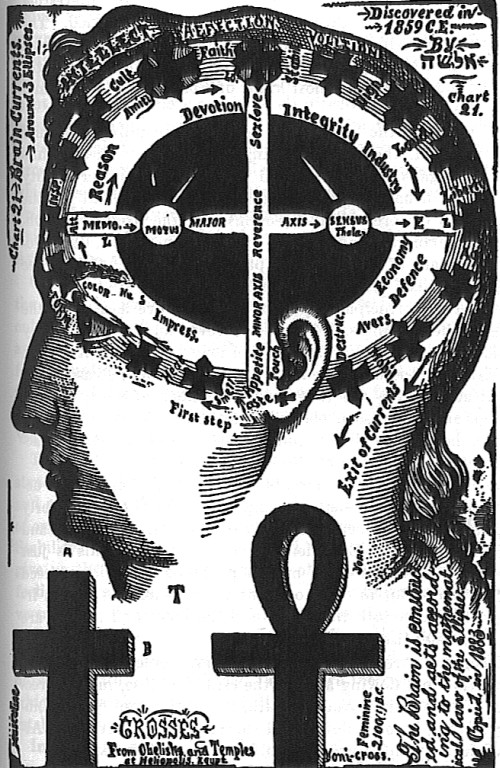

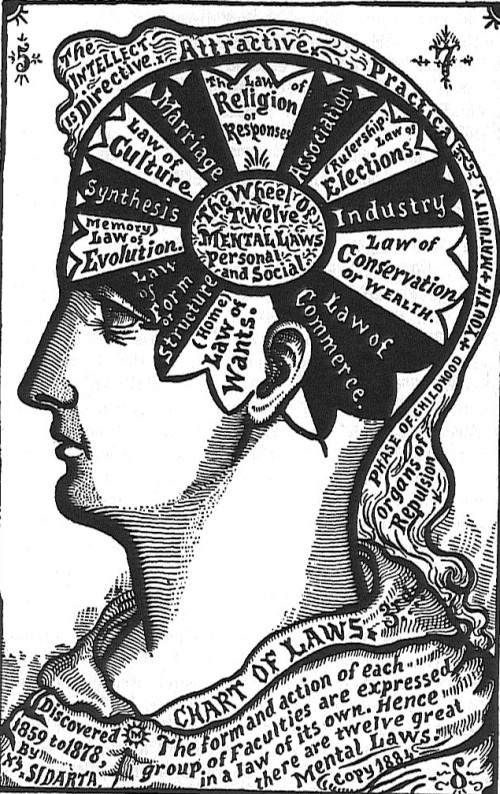

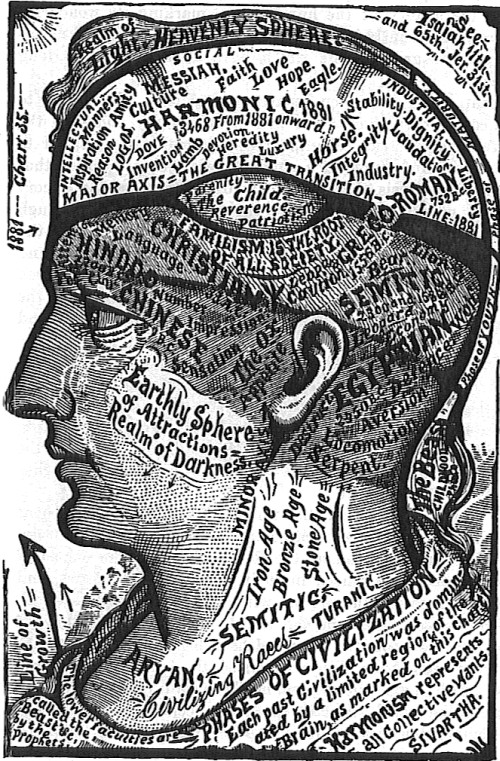

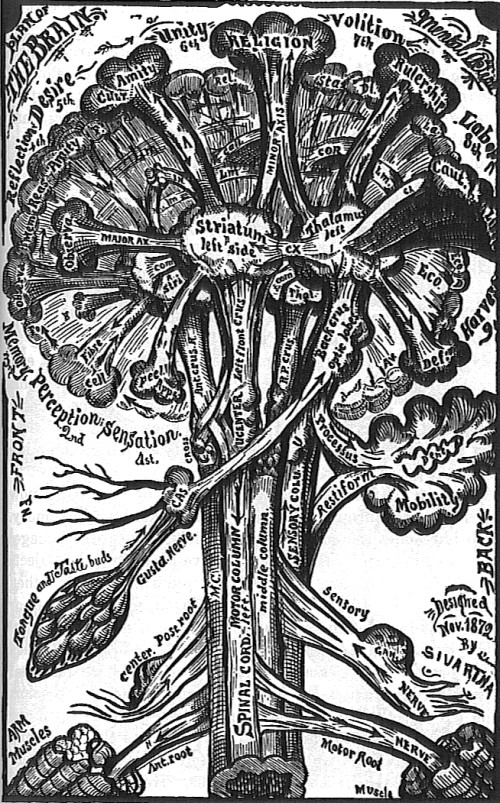

(All images above by Dr. Alesha Sivartha, The Book of Life)

has someone seen my razor?

http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Navalha_de_Occam

&

http://www.cartacapital.com.br/edicoes/2007/02/431/referencia-fast-food/