Tava conversando com Octavio sobre alienação/erudição em referências culturais “urbanas-cosmopolitas-contemporâneas” na “MÚSICA”, e como elas não podem em alguns casos (quase na tentativa de uma genealogia de identidade) simplesmente serem classificadas como parte/resultado da indústria cultural, e é impossível dissociar a dimensão humana envolvida da iconografia espetacular em suas várias dimensões… eu pelo menos considero que meu folclore e noção de subjetividade estão inevitavelmente viciados nessas referências e que talvez assim eu posso tentar definir algum tipo de mapa onde transito…

por pura preguiça e por achar que vale mais a pena discutir isso num boteco, eu vou colar aqui algumas sinapses interessantes que aparecem surfando no allmusic.com e suas quase arbitrárias definições de “genêro musical”, só pra confundir quem duvida desta pluralidade ( não que eu ache que ta tudo perfeitamente definido ali , mas tem referências curiosas).

—–>

Sludgy, abrasive, and punishing, Noise is everything its name promises, expanding on the music’s capacity for sonic assault while almost entirely rejecting the role of melody and songcraft. From the ear-splitting, teeth-rattling attack of Japan’s Merzbow to the thick, grinding intensity of Amphetamine Reptile-label bands like Tar and Vertigo, it’s dark, brutal music that pushes rock to its furthest extremes. By the end of the ’90s, a resurgence in the use of sine waves — originally explored by musique concrí¨te artists in the ’50s — became increasingly frequent among noise artists such as Otomo Yoshihide.

;;;;

Avant-Garde is taken from the French for “vanguard,” which is the part of the armed forces that always stands at the front of the rest of the army. In the case of music, the avant-garde are those individuals who take music to the next step in development or at least take music on a divergent path. The term was first applied only after World War II. In popular idioms it is a term used to describe or refer to free jazz movements but the meaning remains the same: techniques of expression that are new, innovative and radically different from the tradition or the mainstream. Wagner and Debussy can easily be classified as avant-garde relevant to their time but the term did not enter familiar usage until the advent of Stockhausen.

;;;;;;;

Avant-Garde Jazz differs from free jazz in that it has more structure in the ensembles (more of a “game plan”) although the individual improvisations are generally just as free of conventional rules. Obviously there is a lot of overlap between free jazz and avant-garde jazz; most players in one idiom often play in the other “style” too. In the best avant-garde performances it is difficult to tell when compositions end and improvisations begin; the goal is to have the solos be an outgrowth of the arrangement. As with free jazz, the avant-garde came of age in the 1960s and has continued almost unnoticed as a menacing force in the jazz underground, scorned by the mainstream that it influences. Among its founders in the mid-to-late ’50s were pianist Cecil Taylor, altoist Ornette Coleman and keyboardist-bandleader Sun Ra. John Coltrane became the avant-garde’s most popular (and influential) figure, and from the mid-’60s on, the avant-garde innovators made a major impact on jazz, helping to push the music beyond bebop.

;;;;;;;;

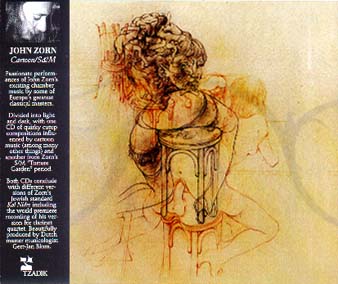

Continuing the tradition of the ’50s to ’60s free-jazz mode, Modern Creative musicians may incorporate free playing into structured modes — or play just about anything. Major proponents of modern creative jazz include John Zorn, Henry Kaiser, Eugene Chadbourne, Tim Berne, Bill Frisell, Steve Lacy, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, and Ray Anderson.

;;;;;;;;

Atonal is music with no key-centeredness, dominant tone or diatonic scale associated with it, and is often considered disconcerting by those who are accustomed to “traditional” harmonies. Melodies, if they can be discerned at all, are generally self-contained and not related externally to any other piece of music, structurally or otherwise. This characteristic can also be ascribed to the harmonies involved in the atonal work. Key-signatures, an exterior structure, are present in tonal music but completely absent in atonal works. In twelve-tone scales for example, each note is given an inherent value equal to that of any other tone. Some twelve-tone composers have required that each note of a twelve-tone scale be used once and only once until all of the tones have been used, then the method continues but the phrase is not repeated. As composers, Berg and Schoenberg are often exemplified as atonal composers.

;;;;;;;;;

The modern eras of composition have been friendly to the composer who broke the rules instead of following them. Speaking in general terms, the music of the last hundred years has not been “generic” — that is, it tends not to fall into conventional genres. Composers have written pieces that are sui generis, or one of a kind. The forms, instruments, and ensembles used in music of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have a dazzling range that in fact is one of avant-garde music’s chief attractions for those stimulated by the shock of the new. One notorious composition of the twentieth century, in fact, used no instrumental sound at all: John Cage’s 4′ 33″ simply instructs “any number of players” to sit for that length of time without playing their instruments; the “music” consists of the ambient noise on which the audience is thus induced to focus. While the manifestation is extreme, the spirit of Cage’s piece is one that animated many of his contemporaries as they explored the nature of musical sound and shape.

;;;;;;;;

Though it was the questioning spirit of the 1960s that gave full free rein to the avant-garde philosophical imagination, the roots of the movement extend back to the World War I era. The sonic experiments of the Italian futurists inspired a host of efforts to create new instruments and generally to bring new sounds to the musical arena. The 1920s all-percussion works of the Franco-American composer Edgard Varí¨se still sound well ahead of their time, and new 1920s instruments such as the theremin, the vocal-sounding contraption immortalized in the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations,” forecast an entire tradition of all-electronic compositions later in the century. The ultra-ambitious German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen was one of the earliest and most successful experimenters with electronic sound.

Though the term “avant garde” carries the implication that a work so described is “ahead of the pack,” the avant garde gave birth to a genuinely popular movement in the last third of the twentieth century. Minimalist music, which in its pure form featured the reiteration and gradual alteration of single musical ideas over long stretches of time, had its beginnings in the heady 1960s. One of the minimalist movement’s earliest figures also became perhaps its most popular: Steve Reich introduced the experimental technique of allowing tape loops to slip slightly out of phase with each other in such works as It’s Gonna Rain (1966), which featured a sermon by a San Francisco street preacher. As listeners from outside traditional classical circles began to tune into minimalism, Reich and other composers began to create larger works. Philip Glass’s stage trilogy of the late 1970s and 1980s, comprising Einstein on the Beach, Satyagraha, and Akhnaten, cemented his reputation as a composer with avant-garde beginnings and a wide popular reach.

;;;;;;;;

As computer-aided composition slowly eclipsed the traditional analog approach to crafting electronica, the palette of possible sounds soon widened immensely, resulting in the advent of the glitch style in the late ’90s. No longer was the artist confined to sequenced percussion, synth, and samples, but rather any imaginable sound, including the uncanny realm of digital glitches — a possibility that was quickly exploited by a generation of youths with the means to create entire albums in their bedroom with only a computer and some software. Where early-’90s analog-toting pioneers such as Aphex Twin and Autechre had envisioned the quickly diminishing areas of electronica that had not yet been explored, and simultaneously, another insular group of pioneers led by Robert Hood and Basic Channel stripped away the elements of electronica that had ultimately become little more than ineffective cliché, a second wave of computer-armed protégés studied these aesthetics and used software to create microscopically intricate compositions harking back to these pioneers. First championed by the ideological German techno figure Achim Szepanski and his stable of record labels — Force Inc, Mille Plateaux, Force Tracks, Ritornell — this tight-knit scene of experimental artists creating cerebral hybrids of experimental techno, minimalism, digital collage, and noise glitches soon found themselves being assembled into a community. Though artists such as Oval, Pole, and Vladislav Delay, among others, had initially been singled out by critics beforehand, Mille Plateaux’s epic Clicks_+_Cuts compilation first defined the underground movement, exploring not only a broad roster of artists but also a wide scope of approaches. The artists on the compilation, along with a small community of visionary artists in the software-savvy San Francisco/Silicon Valley area of California led by the Cytrax label, soon found themselves as the critically hailed leaders of yet another electronica movement. It wasn’t long before the glitch aesthetic began being crossbred with existing genres, resulting in endless variations on the aesthetic, such as MRI’s click-driven house and Kid 606’s noise remix of N.W.A’s “Straight Outta Compton.”

;;;;;;;;;;

Largely defined by its own name, the term microsound largely stems from compositions built on sounds lasting no longer than a thousandth of a second, but generally can last up to a tenth of a second. A cousin to the glitch genre, microsound explores the lower and higher frequencies of the sound spectrum through digital and analog signal processing, granular synthesis, and micromontage. It focuses largely on the arrangement of sound particles within a composition.

;;;;;;;;;;;

The father of Musique Concrí¨te, French composer Pierre Schaeffer, was among the most visionary artists of the postwar era. Through the creation of abstract sound mosaics divorced from conventional musical theory, he pioneered a sonic revolution which continues to resonate across the contemporary cultural landscape, most deeply in the grooves of hip-hop and electronica. Born in 1910, Schaeffer was not a trained musician or composer, but was instead working as a radio engineer when he founded the RTF electronic studio in 1944 to begin his first experiments in what would ultimately be dubbed musique concrí¨te. Working with found fragments of sound — both musical and environmental in origin — he assembled his first tape-machine pieces, collages of noise manipulated through changes in pitch, duration, and amplitude; the end result heralded a radical new interpretation of musical form and perception.

In October 1948, Schaeffer broadcast his first public piece, “Etude aux Chemins de Fer,” over French radio airwaves; although the public reaction ranged from comic disbelief to genuine outrage, many composers and performers were intrigued, among them Pierre Henry, who in 1949 joined the RTF staff, as well as future collaborators Luc Ferrari and Iannis Xenakis. (Olivier Messiaen was also a guest, bringing with him students Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez.) Schaeffer forged on, in 1948 completing “Etude Pathetique,” which in its frenetic mix of sampled voices anticipated the emergence of hip-hop scratching techniques by over a generation; by 1949’s “Suite pour 14 Instruments,” he had turned to neo-classical textures, distorted virtually beyond recognition. In 1950, Schaeffer and Henry collaborated on “Symphonie pour un homme seul,” a 12-movement work employing the sounds of the human body.

Working with the classically trained Henry on subsequent pieces, including “Variations Sur une Flute Mexicaine” and “Orphee 51,” clearly informed Schaeffer’s later projects, as he soon adopted a more accessible musical approach. Together, the two men also co-founded the Groupe de Musique Concrí¨te in 1951; later rechristened the Groupe de Recherches Musicales, or GRM, their studio became the launching pad behind some of the most crucial electronic music compositions of the era, among them Edgard Varí¨se’s “Deserts.” However, by the end of the decade most of the GRM’s members grew increasingly disenchanted with the painstaking efforts required to construct pieces from vinyl records and magnetic tape; after later, tightly constructed works like 1958’s “Etude aux Sons Animes” and the next year’s “Etudes aux Objets,” even Schaeffer himself announced his retirement from music in 1960.

Leaving the GRM in the hands of Francois Bayle, some months later Schaeffer founded the research center of the Office of French Television Broadcasting, serving as its director from 1960 to 1975; in 1967, he also published an essay titled “Musique Concrí¨te: What Do I Know?” which largely dismissed the principles behind his groundbreaking work, concluding that what music now needed was “searchers,” not “auteurs.” In later years, Schaeffer did explore areas of psycho-acoustic research which he dubbed Traite de Objets Musicaux (TOM); these experiments yielded one final piece, the 11-minute “Le Triedre Fertile.” He also hit the lecture circuit and agreed to produce radio presentations. Pierre Schaeffer died in Aix-en-Provence on August 19, 1995

;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;

–>

Algumas categorizações do rock – esse veneno da máquina do entretenimento pós-industrial ( que provam que ou os “eruditos-urbanos” deliram ou realmente existem espectros de “profundidade” na música “popular” – destaquei alguns subgenêros que me identifico – ) -> obviamente são definições anglocêntricas… mas como falei… to com preguiça de relativizar… uma excelente referencia de história do rock brasileiro ( e algum panorama do cenário atual) pode ser encontrada em http://www.senhorf.com.br/

Rock Styles

Alternative/Indie-Rock

* Industrial

* Alternative Pop/Rock

* Goth Rock

* Lo-Fi

* Grunge

* Shoegaze

* Britpop

* Post-Rock/Experimental

* Funk Metal

* Indie Rock

* Paisley Underground

* Jangle Pop

* Alternative Country-Rock

* Punk Revival

* Post-Grunge

* Third Wave Ska Revival

* Neo-Psychedelia

* Riot Grrrl

* Space Rock

* Adult Alternative Pop/Rock

* Alternative Dance

* Cocktail

* Dream Pop

* Punk-Pop

* British Trad Rock

* Industrial Dance

* Madchester

* Psychobilly

* Ska-Punk

* Cowpunk

* New Zealand Rock

* Chamber Pop

* Twee Pop

* Emo

* Slowcore

* Electro-Industrial

* Ambient Pop

* C-86

* Indie Pop

* Noise Pop

* Math Rock

Math Rock is a relation to post-rock, a better known indie-rock style that shares similar aesthetics. Where post-rock has distinct jazz influences, math rock is the opposite side of the same coin — it’s dense and complex, filled with difficult time signatures and intertwining phrases. Also, the style is a little more rockist than post-rock, since it’s usually played by small, guitar-led bands. Math rock peaked in the mid-’90s, when groups like Polvo and Chavez had small, dedicated followings among indie rockers on collegiate campuses.

* Queercore

* Sadcore

* Shibuya-Kei

* Skatepunk

* Garage Punk

* Alternative Folk

* Neo-Glam

* College Rock

* Pop Underground

* American Underground

* Indie Electronic

Art-Rock/Experimental

* Prog-Rock/Art Rock

* Kraut Rock

* Noise-Rock

Noise-Rock is an outgrowth of punk rock, specifically the sort of punk that expressed youthful angst and exuberance through the glorious racket of amateurishly played electric guitars. Noise-rock, like its forerunner no wave, aims to be more abrasive, sometimes for comic effect and sometimes to make a statement, but always concentrating on the sheer power of the sound. While most noise-rock bands concentrate on the ear-shattering sounds that can be produced by distorted electric guitars, some also use electronic instrumentation, whether as percussion or to add to the overall cacophony. Some groups are more concerned than others about integrating their sonic explorations into song structures; pioneers Sonic Youth helped bring noise-rock to a wider alternative-rock audience when they began to incorporate melody into their droning sheets of sound. Sonic Youth produced a bevy of imitators, but not all noise-rock resembles their music — ’80s bands like the Swans and Big Black took a much darker, more threatening approach, and the Touch & Go label became a center for crazed, shock-oriented takes on the style in the late ’80s and ’90s. A certain theatrical sub-style of noise-rock, often described as “scuzz-rock” or with similar terms, uses the guitar noise to help create a dirty, decadent, repulsive atmosphere (bands like this include Royal Trux, Pussy Galore, the Dwarves, and the Butthole Surfers).

Post-rock was the dominant form of experimental rock during the ’90s, a loose movement that drew from greatly varied influences and nearly always combined standard rock instrumentation with electronics. Post-rock brought together a host of mostly experimental genres — Kraut-rock, ambient, prog-rock, space rock, math rock, tape music, minimalist classical, British IDM, jazz (both avant-garde and cool), and dub reggae, to name the most prevalent — with results that were largely based in rock, but didn’t rock per se. Post-rock was hypnotic and often droning (especially the guitar-oriented bands), and the brighter-sounding groups were still cool and cerebral — overall, the antithesis of rock’s visceral power. In fact, post-rock was something of a reaction against rock, particularly the mainstream’s co-opting of alternative rock; much post-rock was united by a sense that rock & roll had lost its capacity for real rebellion, that it would never break away from tired formulas or empty, macho posturing. Thus, post-rock rejected (or subverted) any elements it associated with rock tradition. It was far more concerned with pure sound and texture than melodic hooks or song structure; it was also usually instrumental, and if it did employ vocals, they were often incidental to the overall effect. The musical foundation for post-rock crystallized in 1991, with the release of two very different landmarks: Talk Talk’s Laughing Stock and Slint’s Spiderland. Laughing Stock was the culmination of Talk Talk’s move away from synth-pop toward a moody, delicate fusion of ambient, jazz, and minimalist chamber music; Spiderland, meanwhile, was full of deliberate, bass-driven grooves, mumbled poetry, oblique structures, and extreme volume shifts. While those two albums would influence many future post-rock bands, the term itself didn’t appear until critic Simon Reynolds coined it as a way to describe the Talk Talk-inspired ambient experiments of Bark Psychosis. The term was later applied to everything from unclassifiable iconoclasts (Gastr del Sol, Cul de Sac, Main) to more tuneful indie-rock experimenters like Stereolab, Laika, and the Sea and Cake (not to mention a raft of Slint imitators). Post-rock came into its own as a recognizable trend with the Chicago band Tortoise’s second album, 1996’s Millions Now Living Will Never Die, perhaps the farthest-reaching fusion of post-rock’s myriad touchstones. Suddenly there was a way for critics to classify artists as diverse as Labradford, Trans Am, Ui, Flying Saucer Attack, Mogwai, Jim O’Rourke, and their predecessors (though most hated the label). Post-rock quickly became an accepted, challenging cousin of indie rock, centered around the Thrill Jockey, Kranky, Drag City, and Too Pure labels. Ironically, by the end of the decade, post-rock had itself acquired a reputation for sameness; some found the style’s dispassionate intellectuality boring, while others felt that its formerly radical fusions had become predictable, partly because many artists were offering only slight variations on their original ideas. However, even as the backlash set in, a newer wave of bands (the Dirty Three, Rachel’s, Godspeed You Black Emperor!, Sigur Rós) gained wider recognition for their distinctive sounds, suggesting that the style wasn’t exhausted after all.

No Wave was a short-lived, avant-garde offshoot of ’70s punk, based almost entirely in New York City’s Lower East Side from about 1978-1982. Like the post-punk movement that was primarily centered in Britain, no wave drew from the artier side of punk — but where British post-punk was mostly cold and despairing, no wave was harsh, abrasive, and aggressively confrontational. Most no wave bands were fascinated by the pure noise that could be produced by an electric guitar, making it an important component of their music (and oftentimes the central focus). Unlike punk, melody was as unimportant as instrumental technique, as most no wavers concentrated on producing an atonal, dissonant (yet often rhythmic) racket. With its assaultive artiness and theatrical angst, no wave was as much performance art as it was music. Two of no wave’s central figures were vocalist/guitarist Lydia Lunch and saxophonist James Chance, who performed together in Teenage Jesus and the Jerks; Lunch went on to a long solo career, and Chance formed an innovative no wave/funk outfit called the Contortions. The defining no wave recording is the 1978 Brian Eno-produced compilation No New York, which features material from Chance and the Contortions, Teenage Jesus, DNA (featuring avant-garde guitarist Arto Lindsay), and Mars. Although none of the no wave performers ever really broke out to wider audiences (Lunch’s prolific, collaboration-heavy solo output brought her the closest), Sonic Youth fused no wave’s distorted cacophony with the more meditative noise explorations of guitarist/avant-garde composer Glenn Branca, and became underground legends after adding more melodic structure to the sound.

* Neo-Prog

* Experimental Rock

* Canterbury Scene

* Avant-Prog

Folk/Country Rock

* Country-Rock

* Folk-Pop

* Singer/Songwriter

* Folk-Rock

* British Folk-Rock

Hard Rock

* Blues-Rock

* Christian Metal

* Hard Rock

* Southern Rock

* Thrash

* Death Metal/Black Metal

* Glam Rock

* Grindcore

While the term Grindcore has often been used somewhat interchangeably with death metal, the two started out as very different, albeit similarly extreme, forms of music, despite becoming more alike over the years. When it first appeared in the mid-’80s, grindcore in its purest form consisted of short, apocalyptic blasts of noise played on standard heavy metal instrumentation (distorted guitar, bass, drums). Although grindcore wasn’t just randomly improvised, it certainly didn’t follow conventional structure, either; while riffs could sometimes be picked out, pure grindcore never featured verses, choruses, or even melodies. Grindcore vocals sounded torturous, ranging from high-pitched shrieks to low, throat-shredding growls and barks; although the lyrics were usually quite verbose, they were very rarely intelligible. Grindcore’s jaw-dropping aggression was so over the top that pointing to its roots in thrash metal and hardcore punk hardly gives an idea of what it actually sounds like. Indisputably, the band that invented grindcore was Napalm Death, whose 1987 debut album Scum is also perhaps the most representative example of the style. In Napalm Death’s hands, grindcore was actually rather arty, a sonic metaphor for the bleakness, violence, and decay of modern society; the group’s lyrics were additionally packed with angry social commentary. More extreme in the lyrical department was Carcass, the only other band to really epitomize the original grindcore sound; their gruesome, gory rants were literally taken from anatomical textbooks for maximum shock (and gonzo comedy) factor. However, grindcore’s original form was inherently limiting, and its intensity could easily turn into self-parody; on Napalm Death’s second album, they had already begun to experiment with industrial textures, a fusion that would prove popular not only with bands who loved the jackhammer rhythms a drum machine could provide, but also with slower, moodier bands like Godflesh (itself a Napalm Death offshoot). Grindcore’s blistering intensity was assimilated not only into underground heavy metal, but also into avant-garde and experimental music circles; Japanese noise bands like the Boredoms and Merzbow found it inspiring, and jazz musician John Zorn formed the grindcore-inspired group Painkiller (which featured former Napalm Death drummer Mick Harris). Although pure grindcore was a distinctly British phenomenon, the early albums by the Florida band Death — which ratcheted up the aggression and morbidity of prime Slayer — had a raw, crude, assaultive quality that made them extremely similar. Apart from adopting the low, demonic growl of the grindcore vocal style almost wholesale, American death metal bands with relatively limited technical ability who played at fast tempos often resembled grindcore outfits with song structures. In fact, by the ’90s, Napalm Death’s sound was virtually impossible to separate from either death metal or grindcore, and Carcass had become a full-fledged, even melodic, death metal band. One of the very few bands to stick with grindcore’s original form was A.C. (aka Anal Cunt), which primarily employed it to a snottily humorous effect.

* Heavy Metal

* Speed Metal

* Hair Metal

* Arena Rock

* Alternative Metal

* British Metal

* Boogie Rock

* Industrial Metal

* Rap-Metal

* Guitar Virtuoso

* Progressive Metal

* Neo-Classical Metal

* Album Rock

* Aussie Rock

* Pop-Metal

* Rap-Rock

* New Wave of British Heavy Metal

* Detroit Rock

* Glitter

* Punk Metal

* Stoner Metal

* Scandinavian Metal

* Goth Metal

* Doom Metal

* Symphonic Black Metal

* Sludge Metal

* Power Metal

Pop/Rock

* Christian Rock

* Pop

* Pop/Rock

* Girl Group

* Bubblegum

* Teen Idol

* Brill Building Pop

* Comedy Rock

* Baroque Pop

* Sunshine Pop

* AM Pop

* Celebrity

Punk/New Wave

* Synth Pop

* Punk

* Alternative Pop/Rock

* Hardcore Punk

* New Wave

* Power Pop

* Ska Revival

* Mod Revival

* Post-Punk

* New Romantic

* No Wave

* Proto-Punk

* Oi!

* Garage Rock Revival

* British Punk

* Christian Punk

* New York Punk

* L.A. Punk

* American Punk

* Straight-Edge

* Anarchist Punk

* Sophisti-Pop

* College Rock

* Post-Hardcore

Rock & Roll/Roots

* Rock & Roll

* Blues-Rock

* Tex-Mex

* Instrumental Rock

* Rockabilly

* Roots Rock

* Surf

* Pub Rock

* Hot Rod

* Rockabilly Revival

* Surf Revival

* Swamp Pop

* American Trad Rock

* Jam Bands

* Heartland Rock

* Frat Rock

* Hot Rod Revival

* Retro-Rock

* Latin Rock

* Bar Band

Soft Rock

* Singer/Songwriter

* Adult Contemporary

* Soft Rock

* Pop/Rock

Psychedelic/Garage

* Psychedelic

* Garage Rock

* Acid Rock

* Psychedelic Pop

* British Psychedelia

* Obscuro

* Acid Folk

Europop

* Euro-Pop

* Euro-Rock

* Swedish Pop/Rock

Foreign Language Rock

* Rock en Espaí±ol

* French Pop

* Foreign Language Rock

* Italian Pop

* Asian Pop

* Japanese Pop

* Japanese Rock

* Hong Kong Pop

* French Rock

* Aboriginal Rock

British Invasion

* British Invasion

* Psychedelic

* Merseybeat

* British Blues

* Mod

* British Psychedelia

* Freakbeat

* Early British Pop/Rock

Rock & Roll is often used as a generic term, but its sound is rarely predictable. From the outset, when the early rockers merged country and blues, rock has been defined by its energy, rebellion and catchy hooks, but as the genre aged, it began to shed those very characteristics, placing equal emphasis on craftmanship and pushing the boundaries of the music. As a result, everything from Chuck Berry’s pounding, three-chord rockers and the sweet harmonies of the Beatles to the soulful pleas of Otis Redding and the jarring, atonal white noise of Sonic Youth has been categorized as “rock.” That’s accurate — rock & roll had a specific sound and image for only a handful of years. For most of its life, rock has been fragmented, spinning off new styles and variations every few years, from Brill Building Pop and heavy metal to dance-pop and grunge. And that’s only natural for a genre that began its life as a fusion of styles.

;

;

;

Process-Generated music refers to music that is a direct result of any process not traditionally used in music composition. The chosen notes do not result from a thought-of melody, or even a systematic deviation off an existing melody, but instead are the result of value-assigning in programs or simulations, or are composed according to structures other than musical forms. For example, process-generated can refer to computer-generated sound patterns, whether the computer is programmed to generate tones randomly, or to structure sound according to biological processes, scientific principles, and so on.

——-

When you feel it’s not really music anymore, it’s probably sound art. The expression refers to an esthetic approach in which the artist considers sound — noise or “sound events,” as opposed to notes — as a prime material to create a work of art. Sound art can be the wailing of a tub with strings (Stephen Froyleks), the recordings of the variations in the bioelectrical fields of plants (Michael Prime), the sound of a microphone “writing” on a metal book (Pierre-André Arcand), or abstract sound paintings. It can be of acoustical or electronic nature, but in general the source sounds have been treated through studio manipulation (without resorting to musique concrí¨te techniques) or emanate from one-of-a-kind instruments. The accessibility of electronic instruments and computers in the 1980s and 1990s stemmed more and more cross-pollination between electronica and musique concrí¨te, the resulting music often falling in the “sound art” category in lack of a better term.

Ã?Ë? isso aÃ? Glerm! Interessante observar o tipo de aproximaÃ?§Ã?£o que houve entre as pesquizas vanguardistas da mÃ?ºsica eletroacÃ?ºstica e as expressÃ?´es populares do rock. valeu!

o trecho do post-rock acabou repetindo

Banda financia CD de estr�©ia vendendo a�§�µes

IAN YOUNGS

da BBC Brasil

Um punhado de f�£s do grupo de indie rock brit�¢nico Four Day Hombre tem muito interesse em que o �¡lbum de estr�©ia da banda seja um sucesso porque usaram a pr�³pria poupan�§a para comprar a�§�µes da gravadora.

Cerca de 30 dedicados f�£s do grupo, da cidade de Leeds, no norte da Inglaterra, investiram no CD Experiments in Living, que chega � s lojas nesta segunda-feira.

Alguns apostaram milhares de libras no selo criado pela banda, que tentou sem sucesso fechar contratos com gravadoras.

E o investimento pode comeÃ?§ar a dar dividendos, com o tablÃ?³ide britÃ?¢nico The Sun dizendo que o som do grupo “fica entre o do Coldplay e do Radiohead”.

HÃ?¡ dois anos e meio, o Four Day Hombre recebeu ofertas de contratos com gravadoras, mas as propostas nÃ?£o ofereciam vantagens financeiras nem controle artÃ?Âstico.

“Chegamos perto de assinar contratos com grandes gravadoras, depois tentamos um selo independente, mas nada deu certo”, disse o cantor do grupo, Simon Wainwright.

“Decidimos que tÃ?Ânhamos de seguir em frente, conseguir o dinheiro de uma forma ou outra e abrir nosso prÃ?³prio selo. Ou desistir de uma vez.”

Pedidos por e-mail

O grupo mandou e-mails pedindo aos f�£s que comprassem a�§�µes do selo da banda.

A gravadora Alamo Music foi criada e o grupo fechou com si mesmo contrato para a grava�§�£o de tr�ªs �¡lbuns.

“Acabamos levantando muito mais dinheiro do que terÃ?Âamos recebido de um bom selo independente”, disse Wainwright.

“As pessoas realmente nos apÃ?³iam – Ã?© inacreditÃ?¡vel. Algumas literalmente nos deram dinheiro que economizaram a vida inteira. SÃ?³ espero que nÃ?£o dÃ?ª errado.”

N�£o �© a primeira vez que f�£s financiam seus artistas favoritos na hist�³ria da ind�ºstria fonogr�¡fica.

F�£s do grupo de rock progressivo brit�¢nico Marillion financiaram os dois �ºltimos �¡lbuns da banda.

Tietes do roqueiro londrino John Otway pagaram at�© US$ 12 mil para financiar sua turn�ª mundial.

A diferen�§a �© que, nesses dois casos, os artistas j�¡ tinham carreiras estabelecidas e um s�³lido f�£-clube.

O brit�¢nico Ben Denison, um especialista em inform�¡tica de 28 anos, investiu por volta de US$ 4,6 mil no Four Day Hombre.

“Tive de pedir aprovaÃ?§Ã?£o da namorada primeiro – a opÃ?§Ã?£o era uma cozinha nova ou aÃ?§Ã?µes de uma gravadora independente”, explica Denison.

F�£s que investem em suas bandas favoritas t�ªm maior interesse em promover o trabalho do grupo no boca a boca.

Denison ajudou a criar um grupo de divulga�§�£o da banda.

Ele diz que est�¡ consciente dos riscos e sabe que pode perder seu investimento.

“Mas espero receber de volta uma boa experiÃ?ªncia na indÃ?ºstria fonogrÃ?¡fica e muita diversÃ?£o.”

Se o �¡lbum fizer sucesso, os investidores v�£o receber uma parte dos lucros.

“No fundo, existe sempre aquela esperanÃ?§a de que as coisas dÃ?ªem muito certo”.